Fall 2008 A publication of the Wildlife Diversity Program—Getting Texans Involved

Grasslands:

Treasures Lost and (re)Found

By Mark Klym

Much of Texas was once described as grasslands, from our noted prairie regions like the Blackland Prairies and the Gulf Coast Prairies and Marshes, to those not so obviously named like the Edwards Plateau, much of which would be prairie interspersed with canyons, or the Trans Pecos where grasslands are common at lower elevations. These prairies quickly became the "bread basket of the world" as Europeans settled the land and put it to plow or pasture. The mosaic of grasses and wildflowers soon became a monoculture of crops or became degraded by an invasion of oportunistic vegetation. Prairies are now recognized as some of the ecosystems causing the most concern among naturalists in Texas today. The Texas Wildlife Action Plan completed in 2006 shows prairies as 2 of the 3 high priority ecoregions for the state and 3 of the 4 secondary priority regions.

A great proportion of the concern has developed as we have watched the rapid transition associated with the encroachment of urban landscapes into the colorful palet that were our native prairies. Grasslands are more than just waving grasses or colorful mosaics – they are home to a very diverse, specialized collection of flora and fauna. Diverse species of bird, mammal, insect and plant are imperiled as habitat becomes cities, crops, etc.

This volume of Eye on Nature focuses on the grassland, and what is being done to understand, restore and conserve these unique ecosystems. In this volume you will find an article that describes one of the many state parks on our prairies, an article about some of the help available to landowners wanting to conserve grassland and other habitat, an article about volunteer monitoring oportunities for wildlife of concern in the grasslands and other interesting features.

A landscape approach to

upland bird conservation

By Jay Whiteside

Until the late 1970's or early 1980's, the sound of "Bob-bob-whiiiiite" was as much of a springtime passage in Navarro County as the annual bloom of wildflowers. During this time, the bobwhite whistles slowly began to fade. By the late 1980's they had become all but silent. Today, except in small isolated habitat patches in the western portion of the county, the springtime silence continues. If you're lucky, and happen to be in the right place at the right time, you just might hear one, but it is almost like finding a needle in a haystack. When you do hear one you are so surprised that you second guess yourself.

What, happened to the bobwhites? Many farmers and ranchers want to place the blame solely on the invasion of the red imported fire ant, or increased abundance of predators due to reduced hunting and trapping that resulted from the collapse of the fur market. However, Navarro County is not alone. Over the past 30 to 40 years, bobwhite populations have dramatically declined range wide. This includes portions of their range where red imported fire ants have not invaded and predator abundance is relatively low compared to that of Navarro County. Additionally, there are portions of Texas where bobwhites are thriving despite the presence of red imported fire ants, and/or very high predator abundance. If it is not the invasion of the red imported fire ant, or increased predator abundance, what could it be? Most quail experts agree on one thing; the range wide bobwhite decline over the past 30 to 40 years is a result of habitat loss and fragmentation. This theory is reinforced by similar population declines in other bird species, most notably the loggerhead shrike and Eastern meadowlark, which utilize much of the same habitat components as the bobwhite.

Since habitat decline and fragmentation is the driving force behind the rangewide bobwhite decline, what is being done to reverse this alarming trend? In 2001, a group of notable quail scientists known as the Southeastern Quail Study Group, developed a comprehensive rangewide conservation plan. This plan, commonly known as the Northern Bobwhite Conservation Initiative set specific habitat goals and objectives for various ecological regions (Bird Conservation Regions BCR's) throughout the range of the bobwhite aimed at recovering population densities to those in 1980. The development of the Northern Bobwhite Conservation Initiative has set the foundation for bobwhite conservation and today many states, including Texas (Texas Quail Initiative TQI (PDF)), have developed their own step down versions of this plan to address more specific challenges and needs within their respective boundaries.

The Birth of WNBRI

In 2006, Gary Price, a landowner in the Blooming Grove area of Navarro County, asked; "What can be done to bring the quail populations back to what they used to be?" As a wildlife biologist, my obvious answer was; "We need to restore and/or improve habitat for quail over a very large geographic area and focus these efforts around areas where we know quail persist." Our discussion continued and after a while Gary indicated that he felt like the time was right to deliver the habitat conservation message and begin forming a landowner cooperative around his property, where we knew quail persisted, and possibly beyond. I decided that the time was right to move forward with the landowner cooperative idea. Over the next few months I wrote a strategic plan, now known as the Western Navarro Bobwhite Recovery Initiative (WNBRI), to present to this group of landowners.

The WNBRI is a landscape level approach to upland bird conservation that sets specific habitat enhancement goals for a particular geographic area and outlines what needs to be done to achieve those goals. Because habitat loss and fragmentation is the is the primary factor limiting bobwhite populations in western Navarro County, the number 1 goal of the WNBRI is to create contiguous useable habitat for bobwhite over an area of approximately 30,000 acres. The theory behind this concept is that if suitable habitat conditions can be restored, improved, and maintained over an area this large, source populations within the area will have the ability to grow and expand into unoccupied habitat over time, creating a more viable population.

To be able to reach this lofty 30,000 acre goal, it would be necessary to create a mechanism that could pool landowners together, educate them, keep them informed, and keep them engaged in habitat management. The number 2 goal of the initiative was to develop the Western Navarro Bobwhite Recovery Cooperative (WNBRC).

Achieving habitat conservation, particularly native grassland restoration and range improvement, over such a large area is not an easy task, and likely impossible without cooperation and partnerships. The third goal of the WNBRI was to develop partnerships with government organizations and non-profit conservation groups. Developing partnerships with these groups allows the necessary knowledge and resources to achieve the scope of work desired.

WNBRI Moving Forward

The first step in getting the WNBRI wheels in motion, was to pitch the idea to a select group of landowners within the initiative area. In June of 2006, 15 landowners attended a meeting at the USACOE Navarro Mills Lake Project Office where the idea of the WNBRI was presented. A majority of the group decided that the plan was worth pursuing and the Western Navarro Bobwhite Recovery Cooperative was formed. Since that meeting, the WNBRC has grown to 32 active members, and the land base their properties has increased to close to 30,000 acres.

Once the WNBRC was formed and officers elected, the first item of business was to hold a landowner workshop to introduce the WNBRI plan to a larger group of landowners, educate them on bobwhite ecology and management, and enroll new members into the WNBRC. On September 23, 2007 the landowner workshop, titled Bringing Back the Bobwhite, was held at the Blooming Grove Elementary School Cafeteria. The workshop featured presenters from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Audubon Texas, and a private Range and Wildlife Management Consultant. A total of 30 landowners attended the workshop, and 12 new members enrolled in the WNBRC.

The next order of business was to build partnerships within the wildlife conservation community. Two key partnerships were formed prior to the landowner workshop; one with the Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the other with Audubon Texas. Other key partnerships that developed following the workshop were with the Trinity Basin Conservation Foundation, Texas Agrilife Extension Service, and the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers Navarro Mills Lake Project.

Once the two major elements of the WNBRI were in place, the formation of the WNBRC and partnerships with government and non government organizations formed, the next step was putting habitat on the ground. One of the key elements for habitat improvement would be native grassland restoration and range improvement. Audubon Texas made a significant contribution by donating $40,000 worth of native grass and forb seed – enough to plant roughly 1000 acres – to the WNBRC to provide to their members free of charge. The donated native seed mixture has been used to plant 425 acres and about 500 acres are scheduled for planting during the spring of 2009.

Another key contribution came from the Trinity Basin Conservation Foundation (TBCF). In the spring of 2008, the TBCF was awarded a Wildlife Diversity Grant from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to purchase essential equipment for the WNBRC to use in native grassland restoration and range enhancement projects. The equipment that will be donated to the WNBRC includes a no-till seed drill, prescribed burning equipment and trailer for transporting, and herbicide for planting site preparation treatments.

Summary

The WNBRI is still in its infancy. A lot of work still lies ahead for it to achieve its ambitious goals. However, in a little over 2 years it has made some enormous strides and the future looks promising. No one can predict what the future holds for bobwhites and other gassland wildlife in Navarro County. However, we can say for certain that the recovery of the bobwhite and the host of other species that share their habitat will become a distant memory if aggressive habitat conservation efforts, such as the WNBRI, are not undertaken.

Jay is the Wildlife Diversity Biologist working in Navarro County.

Native grassland restoration programs

By Chuck Kowaleski (TPWD) and Susan Baggett (NRCS)

One hundred and fifty years ago much of Texas west of I-45 was a sea of native grass that fed foraging herds of bison, antelope, elk and deer and provided habitat for hundreds of other grassland dependent species of wildlife. Grass health was maintained by the nomadic nature of the large herds of herbivores whose constant movement prevented local overgrazing and periodic lightning or Native American induced fires. Much has changed since that time. The advent of property ownership and fencing has resulted in the confinement of herbivores to limited areas and increased pressure on desirable native plant species. Human settlement also brought with it the elimination of fire. As native species were eliminated, hardier non-native species were introduced that were better suited to the higher grazing pressures. Herbicides, fertilizers and cultivation techniques came along with the introduced forages and helped to maximize production of the monoculture plantings. In the process, populations of many wildlife species that needed native prairie habitats declined drastically as their habitat was degraded or eliminated.

Many Texans are now starting to realize the value of native grasslands both for plant and wildlife diversity and for low input, high quality forage production. But reverting to native plants can be a time consuming and expensive task. It requires a high degree of specialized knowledge to be successful. Fortunately, there are a number of sources of technical expertise and funding available to landowners through current USDA and TPWD programs.

Landowners that are lucky enough to still have native rangeland, even though it may be in poor health due to past management mistakes or brush encroachment, may wish to take advantage of two USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) programs, CTA and EQIP. CTA stands for Conservation Technical Assistance and, as the name implies, provides free technical assistance by trained NRCS conservationists to interested landowners. The Grazing Land Conservation Initiative (GLCI) is part of this program and provides over $2 million annually in technical assistance funding targeted at conservation on range and pasture land. EQIP stands for the Environmental Quality Incentive Program and provides cost share for a wide variety of practices, including those that improve grassland. Since 2007, EQIP has funded brush management on almost 400,000 acres, planted native grass on almost 50,000 acres and performed prescribed burning on over 7,000 acres in Texas. During this period NRCS staff has written EQIP conservation plans for prescribed grazing on almost 320,000 acres and helped pay for almost 1,000 miles of cross fencing to facilitate prescribed grazing. Every year, each county establishes its own priorities for EQIP funding based on the local resource concerns. For information on local priorities and office locations please visit the following website: www.tx.nrcs.usda.gov/programs/EQIP/index.html

Landowners wishing to convert exotic grass pastures back to native grassland might be interested in the Pastures for Upland Bird program offered by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD). For more information please visit the following website: www.tpwd.state.tx.us/landwater/land/habitats/post_oak/upland_game/pub/

Landowners who would like to convert highly erodible or environmentally sensitive cropland into grassland may wish to look into the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) administered by the USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA). While whole field enrollment is only available during announced signups or in certain areas (such as the State Acres for Wildlife Enhancement (SAFE) (PDF) projects located on the middle and upper Texas coast, Rio Grande Valley and northeastern and southwestern panhandle), partial field enrollments that reduce wind and water erosion such as grass buffers, filter strips, riparian buffers, wildlife corridors, grassed waterways and crosswind trap strips are available year round. Click here to locate your nearest FSA or NRCS office: http://offices.sc.egov.usda.gov/locator/app

Landowners who currently have a grazing operation but are worried that it might be lost due to urban or cropland development can protect it through a Grassland Reserve Program (GRP) permanent conservation easement or shorter term rental of development rights. For more information: www.tx.nrcs.usda.gov/programs/GRP/index.html

Landowners wishing to restore native prairies for at-risk species and reduce the impact of invasive species may want to look into the Wildlife Habitat Incentive Program (WHIP). For more information: www.tx.nrcs.usda.gov/programs/whip/index.html

Grassland restoration may seem a daunting task but it is the mark of the true land steward. Fortunately there are a number of sources of technical and financial help to interested landowners get the task accomplished.

Chuck Kowaleski is TPWD's Farm Bill Coordinator. Susan Baggett is NRCS's State Resource Conservationist.

Lake Arrowhead State Park

Built by the city of Wichita Falls as a primary water source, Lake Arrowhead lies approximately fifteen miles southeast of the city in the North Central Plains of Texas. The lake covers roughly 16,400 surface acres and is bordered by 106 miles of shoreline. Lake Arrowhead State Park, on the northwest portion of the lake, boasts 524 acres. Surrounding the lake, the land is mostly semi-arid, gently rolling prairie. Cutting though the northern portion of the park is Sloop Creek, a tributary of the Little Wichita River.

Located on the eastern edge of the Rolling Plains, the park is characterized by undulating grasslands which include Little Bluestem, Indian Grass, and Sideoats Grama. These grasslands have been invaded by mesquite and other species such as cottonwood, hackberry, and wild plum. An abundance of native wildflowers with a variety of colors may be seen. Indian paintbrushes, bluebonnets, primroses, sunflowers, and daisies are among the plant life found within the park boundaries.

In this Prairie biome, diversity abounds with five ecological expanses encompassing the park. This biome supports numerous species, including an assortment of mammals, birds, reptiles, insects, and fish. White-tailed deer, armadillo, coyote, skunk, rabbit, black-tailed prairie dog, and fox are some of the mammalian population. The area is a major fly-way for the Monarch butterfly and a cross-over for migrating birds such as the pelicans, geese, ducks, hummingbirds, Bald Eagle, hawks, and the Sandhill Crane. The banded water snake, grass snake, turtles, horned lizards, legless lizards, as well as water moccasin and rattlesnakes, are often found.

Lake Arrowhead State Park hosts a Black-tailed prairie dog town. The prairie dog entertains watchers and plays an important role in the park's biome. Also featured at the park are approximately five miles of hiking trails, a 300 acre equestrian area, 71 campsites, 44 shaded picnic tables, and an 18 hole disc (Frisbee) golf course. Nesting boxes are provided for Eastern bluebird along the Bluebird Trail.

The lake teems with game fish, including bass, bluegill, carp, catfish, and crappie. Almost every weekend, a fishing tournament takes place. The park offers the "Loan A Tackle Program" in which the park lends fishing tackle to its visitors. The park provides an unsupervised swimming beach, a concrete launching ramp, lighted fishing piers, two fish cleaning stations, and a floating boat dock.

Educational and interpretive programs are available for groups such as teachers and students. Requirements include a minimum of ten persons attending and pre-scheduling through the park headquarters. Aquatic Wild, Project Learning Tree, Texas Rare and Wild, Adopt a Wet Land, Buffalo Soldiers, and other educational programs are available. Continuing education credit for attending many of these programs is available for teachers.

Park programs with which the Master Naturalists are involved include Texas Horned Lizard Watch, Monarch and Mussel Watch, and Hummingbird Roundup. These involve general skills of observation and note-taking. The amount of time a person spends on the project corresponds to the level of involvement. Texas Parks and Wildlife biologists use the data collected to better understand population trends and management needs of various species in the state.

Texas nature tracking on the prairie

By Marsha May

The North American prairie historically ranged from Canada to the Mexican border and from the foothills of the Rocky Mountains to western Indiana and Wisconsin. This prairie is referred to as the Great Plains. Approximately 400,000,000 acres of prairie covered the Great Plains before European settlement. The Great Plains Prairie is divided into three different types of prairies defined by the types of grasses found in each; (1) tallgrass prairie to the east (2) mixed grass prairie in the middle and (3) shortgrass prairie in the west. The Great Plains Prairie extends into Texas and includes parts of Central Texas, parts of West Texas and the Texas Panhandle.

Grasslands are considered among the most endangered ecosystems in North America. The Texas Wildlife Action Plan (TWAP), created by Texas professionals to conserve wildlife and natural places prioritized the various ecoregions and species of concern in Texas. The Blackland Prairie ecoregion, a tallgrass prairie that historically ran along Interstate Highway 35 in Central Texas was identified in the TWAP as a high priority ecoregion. This ecoregion was identified as the most severely altered in the entire state. Most of the Blackland Prairie has been converted to cropland or urban development, and less than one percent remains in an uncultivated state. The shortgrass prairie is another important grassland in Texas. Originating in the Trans Pecos region of West Texas, it extends northward into the High and Rolling Plains ecoregions of the Panhandle. These ecoregions are experiencing a high rate of conversion to crops and fragmentation. Many species of concern call these ecoregions home.

This is where Texas Nature Trackers can play a role. Texas Nature Trackers is a citizen science monitoring effort designed to involve volunteers of all ages and interest levels in gathering scientific data on species of concern in Texas. The goal of this program is to enable long-term conservation of these species and to foster wildlife appreciation among Texas citizens through experiential learning. The Texas Horned Lizard Watch, Texas Amphibian Watch and Texas Black-tailed Prairie Dog Watch are three programs currently available to citizens that directly involve prairie species of concern. Other watch programs under the Texas Nature Tracker umbrella include Texas Hummingbird Round-up, Texas Monarch Watch, Texas Mussel Watch and the Texas Box Turtle Survey.

The Texas Horned Lizard, our official state lizard, is loved by just about every Texan. The historic range of the Texas Horned Lizard covered all but the eastern Pineywoods of Texas. In the last 30 years Texas' favorite lizard has disappeared from the eastern third of Texas and is increasingly rare in Central Texas. Only in West Texas and South Texas do populations seem to be somewhat stable. This animal is a species of concern and is listed by state as threatened. Texas Horned Lizard Watch is a great way for citizens to get involved in "on the ground" data collection and observations of this charismatic critter.

Amphibians are a barometer of the health of environments we all share. Recent reports suggest that up to 40% of amphibian species in the Americas are declining. Texas Amphibian Watch focuses mostly on frogs and toads, collectively called anurans, and due to the tallgrass prairie to the east getting more annual rainfall than the shortgrass prairie in the west, it would seem to make sense that there would be more anuran species in a wetter ecoregion. There are around 15 anurans in Central Texas and only around 10 in Northwest Texas. The only anuran species of concern in these three ecoregions is the secretive Hurter's spadefoot toad. It can only be found in the Blackland Prairie and regions south and east. These toads are seldom seen. It takes a major rain to coax them out of their burrows. Males have a mating call that sounds like a moaning "Waaaah". Texas Amphibian Watch is another way for citizens to get involved and all it takes is a good ear – most of the data collected are the mating calls of frogs and toads.

Black-tailed prairie dogs are an icon of the grasslands. These animals were once common but now occupy less than 1% of their historic range. Prairie dogs are an important part of the prairie ecosystem, their digging aerates and promotes soil formation, they clip brush maintaining the shortgrass prairie and they are a keystone species providing food and shelter for as many as 170 different animals. Data collected through the Texas Black-tailed Prairie Dog Watch is an opportunity for citizens to help widen our understanding of these prairie sentinels.

To find out more about these and other watch programs, go to www.tpwd.state.tx.us/trackers.

Marsha is Nature Trackers Coordinator and works out of Austin headquarters.

Endangered birds of the coastal prairies –

vanishing or recovering?

By Mark Klym

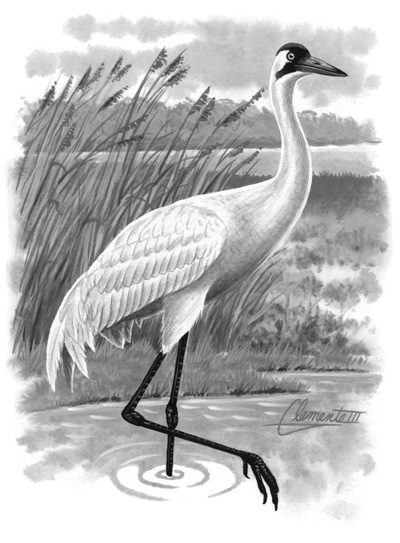

The eerie sounds of a coastal prairie dawn were all but silenced. The mournful "boom" of the Attwater subspecies of Greater Prairie-Chicken have all but disappeared from what was once a 9,500,000 acre crescent of grassland interspersed with herbs and forbs. The pageantry that inspired some Native American dances was nearly gone. And off shore, the majestic Whooping Crane that wintered each season on the intercoastal waterways was quickly disappearing.

A gloomy picture isn't it? But this was the reality of where our coastal prairies were headed. An annual census of Attwater's Prairie-Chickens recently estimated fewer than 40 birds on the two preserves dedicated to their recovery. When serious efforts to restore the Whooping Crane began fewer than 25 birds were thought to populate the flock migrating each year from Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada to Aransas National Wildlife Refuge.

The picture is changing for these two birds though. Efforts to identify and restore habitat for Attwater's Prairie-Chicken are revealing new sites – some on private lands – where captive bred birds are being released. Safe harbor agreements between the Fish and Wildlife Service and landowners with suitable acreage are leading to habitat conservation with potential for population introduction. In 2007 this was realized in Goliad County when prairie chickens were released on private land. In the spring of 2008, the boom of adult Attwater's Prairie-Chickens was restored to the prairies of Goliad County. There are plans for continued releases on this site in 2008. The spring census in 2008 revealed 70 Attwater's Prairie-Chickens between the three populations currently on the Texas coast, nearly doubling the number of the previous spring.

Habitat conservation and harvest restrictions have also contributed to a strong recovery for Whooping Cranes. The most recent flock estimate was 266 birds at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. A spring survey in Canada saw 62% of the estimated flock. These surveys count only birds that have completed their first moult and have spent at least one winter on the wintering grounds.

You can help both of these birds. Captive breeding and release of Attwater's Prairie-Chickens is a costly endeavor and zoos or researchers working with the birds appreciate our support. Donations for prairie-chicken recovery can be made through Adopt-a-Prairie Chicken, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744. Non-profit organizations are currently raising funds to purchase wintering habitat for Whooping Cranes near Aransas National Wildlife Refuge to protect it from development. Reporting any sightings of Whooping Cranes or suspected Attwater's Prairie-Chickens off the refuges is also appreciated. These can be made by emailing mark.klym@tpwd.state.tx.us or leeann.linam@tpwd.state.tx.us.

Other prairie birds are also a major concern as this habitat disappears. The recent Texas Wildlife Action Plan identifies prairie ecosystems, including the coastal prairies, as one of the high priority ecosystems. Bachman's Sparrow, Henslow's Sparrow, Sprague Pipit, Mottled Duck and others are identified as species of high priority within the plan. Much of the concern is specifically directed at habitat loss. Efforts to conserve, identify and restore habitat should be supported if these birds are to continue to be some of the treasures of our vanishing prairies.

Mark is the Information Specialist with the Wildlife Diversity Program working out of the Austin Headquarters.

An introduction to

Texas Turtles

By Mark Klym

Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas Tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi),and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial; others are found only in Marine (salt water) settings. In some countries, like Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal. In North America they are denoted by:

Turtle: an aquatic or semi aquatic animal with webbed feet

Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions

Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of Earth's history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow moving, toothless, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs, and still retain traits they used to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe.

If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. Basking on a log or rock is a convenient way for them to warm their body. Like most ectothermic animals, they do not tolerate radical temperature swings well.

So Why is Texas Home to So Many Turtles?

As with other animal and plant groups found in Texas, our diverse geography, topography and geology has contributed to the diversity in this group. Some of the species found in Texas occupy a very limited range consisting of one or more river drainages. Others, like the ornate box turtle (Terrapene ornata) or red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) are much more widespread, being found over most of the state. The limiting factor with turtles is usually water, so in west Texas these animals may be found only in the river bottoms, while in east Texas, where rivers are more common, they will be more dispersed.

Generally, turtle distribution in Texas is based on watersheds. Range maps of some species look surprisingly like a river map. These species, like the Cagles map turtle (Graptemys caglei) or the Ouachita map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis) are often more adversely impacted by changes in habitat quality than are the more widespread species.

General Turtle Life History

All turtles are egg layers. Females may travel great distances over land in search of suitable soil or leaf litter in which to lay their eggs. Nest sites are often on a sunny slope where the eggs and young, which are not cared for by the mother, can be warmed readily by the sun. Turtle eggs are generally spherical to elongated with shells of varying degrees of hardness.

Even in the nest, temperature can play a vital role in the life of the turtle. Studies have shown that with several species, temperature in the nest will determine the dominant gender of the young – warm nests producing primarily female turtles while cooler nests produced primarily male young.

Eggs and young turtles are eagerly sought prey species for many animals, resulting in most of the young being eaten by birds, raccoons, skunks, mink, coyotes, dogs, and even people. Thus a large number of eggs does not guarantee the survival of the species, nor of a specific genetic line. It also means that some of our turtles, even though they are producing a lot of young, can be very vulnerable.

Turtles are long-lived creatures, with some individuals exceeding 100 years. However, this characteristic can also work against a species, since long-lived animals generally do not mature until later in life. A late maturing animal must survive all the perils and threats for several years before contributing its genes to future generations. In this case, loss of near mature individuals is a significant threat to the future of the species. Unfortunately, near adults are often the very individuals in greatest demand for harvest.

On reaching maturity, a turtle will often travel considerable distances over land in search of nesting sites. This poses yet another danger in the world of the 21st century – collision with cars. Turtles crossing roads are among the wildlife victims of our fast-paced society, often in very significant numbers.

So all in all, the turtle’s life is hardly an easy one – a fact which makes turtles a very special part of our Texas natural history.

Family Accounts

Sea (Marine) Turtles

In Texas we have one species each in four families of sea turtles that visit our shorelines. Loggerheads are generally large turtles with powerful jaws. Their reddish brown heart shaped upper shell helps in their identification. Green sea turtles have a relatively small, lizard like head on a large body. Hawksbills are smaller sea turtles with a sharp, curved bill and numerous splashes of yellow and orange on a red brown shell. Ridley sea turtles in Texas are represented by the Kemp's Ridley sea turtle, one of the smallest of sea turtles with a gray to olive color.

Sea turtles have faced a number of challenges, including the pressure for tortoise shell materials which are collected primarily from Hawksbill sea turtles. Another important factor in sea turtle population decline is human demand for beach areas for recreation – especially during prime sea turtle nesting periods. This was especially critical for the Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle.

Kemp’s Ridley sea turtles are noted for a very unique nesting behavior. Each year, large numbers of these turtles will congregate in “aribadas” just off shore of their nesting beaches. Groups of females will move onshore and lay their eggs enmasse, resulting in a near simultaneous hatch and “predator swamping” by the young turtles returning to the sea. This technique raises the probability that at least one young from each nest will survive.

Close monitoring of known sea turtle nests, turtle exclusion devices on shrimp trawlers, and other conservation efforts have helped to save the sea turtle. In 2007, 128 Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle nests were found on Texas beaches, including 81 on North Padre Island and 4 on Mustang Island.

Green sea turtles are primarily herbivorous, while loggerheads, hawksbills and ridleys feed primarily on invertebrates and mollusks.

Freshwater Turtles

Since they are encountered more frequently than sea turtles, these turtles are more familiar to Texans. The diversity within this group is impressive. Though mostly aquatic, some species spend considerable time out of the water. Mostly vegetarian, there are some species that diet heavily on meat and some that are essentially carnivorous.

Box Turtles

Box turtles are characterized by high, domed shells that are hinged so the animal can completely enclose itself to escape predation. Box turtles have been documented to live up to 50 years, and commonly live to 20 years. There are reports of box turtles achieving 100 years.

In 1995 box turtles were added to the CITES Appendix II. This means that an export permit is required from the country of origin for international trade. Before such permits can be issued, a biological assessment must conclude that such export will not be detrimental to the survival of the species.

Texas is home for three species of box turtles with at least one species being found in any location throughout the state. Desert box turtles are found west of the Pecos River and are a deep brown to reddish brown turtle with very narrow radiating lines on each scute of the carapace. Ornate box turtles are absent west of the Pecos River and, growing a little smaller than the Desert box turtle, have wider yellow radiating lines on their shell. The Three-toed Box Turtle, named for the usual number of toes on the back feet, is found in the eastern portion of the state west to McCulloch and Kimble counties.

In recent years, box turtle numbers have declined. A project tracking box turtles is looking to Texans for reports on where these beautiful animals are found. You can help by completing the form at www.tpwd.state.tx.us/learning/texas_nature_trackers/box_turtle_survey/ each time you see these turtles. Managing your property to produce native forbes and fruit-bearing plants will help to provide habitat for these turtles.

Generally omnivorous, box turtles tend to become more herbivorous with age. Meat items consumed are primarily insects, slugs, snails and carrion, although Three-toed box turtles have been known to consume virtually anything they can get into their mouth. Fish are not mentioned as a significant diet item in any of the papers.

Map Turtles

This diverse group of aquatic turtles occurs from Texas to Florida and north to Quebec and the Dakotas. Most map turtles will have a well defined keel running down the middle of the carapace distinguishing them from the sliders. They generally get their name though for the fine lines decorating the shell and skin, lines that resemble a map.

Five species of map turtle are found in Texas limited to eastern regions of the state west to Throckmorton and Shackelford counties. The Mississippi map turtle, the most widespread of the family, is a brown turtle with a crescent-shaped spot behind the eye and a patterned carapace. Females may be twice the size of males. The Ouachita map turtle is found only along the Red, Neches and Sabine Rivers in east Texas. It is recognized easiest by the three large white blotches behind the eyes. Their head and limbs are decorated by light yellow lines. Generally considered a subspecies of the Ouachita map turtle, the Sabine map turtle is found along the Sabine River between Texas and Louisiana and has two yellow circular spots on top of its head and less noticeable spotting below the eyes. The Texas map turtle is found in fast moving waters of the Colorado River and its drainages from the central Texas Hill Country downstream past Columbus. It is easiest identified by three yellow or orange spots on the bottom of the head. Cagles map turtle is found in eleven counties along the San Antonio, San Marcos and Guadalupe River drainages. They can be identified by numerous cream and yellow lines on the head and the steeply keeled, serrated shell. map turtles are generally insect and mollusk eaters, with some known to consume vegetation. The one reference to fish in the diet referred specifically to dead fish.

Cagles map turtle is on endangered species lists in the state, as state listed threatened species. The Cagles map turtle, while common where it occurs, has a very limited range. Water quality, and flow volumes are critical to this species.

Chicken Turtles

There are three subspecies of this turtle found in the United States only one of which, the Western chicken turtle or Deirochelys reticularia miaria can be found in Texas. It is found in the eastern third of the state at least as far west as the Dallas Fort Worth area where it is found in shallow lakes and drainage ditches. This turtle has a long, narrow head that comes to a point and a long, striped neck.

Chicken turtle populations are considered stable throughout their range, but they are facing a lot of threats including habitat loss, losses to automobile collisions during migration, and loss of foraging areas.

Chicken turtles are omnivorous with a diet that includes crayfish, fish, fruit, invertebrates and plant materials.

Slider Turtles

Found over much of the southeastern US and ranging north into Ohio in the Mid-west, these turtles prefer to feed on vegetation when they mature. They are active throughout the year except for a brief hibernation period which varies in duration depending on climate.

Found statewide, these turtles like slow-moving waters with mud bottoms. Strong currents are generally avoided. While young, sliders eat 70% animal materials, but as they age their diet transitions to about 90% plant material. They eat insects, some fish, plants, tadpoles, crustaceans and mollusks.

There are several species and subspecies of sliders in North America, the Red-eared slider and the Big Bend slider being found in Texas. Red-eared sliders are most easily identified by the red patch, often a stripe, behind the ear. Big Bend sliders have an orange yellow oval bordered in black behind the eye.

Softshell Turtles

Also aggressively sought for commercial trade – more for food markets than the pet industry – are the softshell turtles. These turtles are amazingly camouflaged, with a very flat shell that matches the bottom of the pond or stream perfectly. The shell is also very flexible making them unlike any other turtles.

There are five species of softshell turtles noted from the state. While their individual ranges are somewhat specific, softshelled turtles can be found through most of the state. The Midland smooth softshell is rare in the eastern half of the state but is found in rivers with large sandbars. They lack spines or bumps on their leathery shell, and are the smallest of our softshelled species. The Texas spiny softshell is found in the Rio Grande and Pecos drainages. Whitish spots on the rear third of the carapace are an identifying mark of this turtle. Areas of the Nueces and Guadalupe rivers and their tributaries with only a small amount of aquatic vegetation are home for the Guadalupe spiny softshell. Whitish spots cover the whole carapace of this turtle, sometimes interspersed with small black dots. Found only in the extreme northern panhandle of Texas, the Western spiny softshell prefers waterways with sandy bottoms. This gray or olive turtle has dark spots and a sandpaper like texture to its shell. The carapace is bordered by one dark marginal line. The Pallid spiny softshell is found through most of northeast Texas from the upper Red River drainages and water east of the Brazos River draining into the Gulf. This pale turtle has white tubercles on the back 2/3 of its shell.

Heavy harvesting is causing some concern among biologists over the stability of some softshell turtle populations. Softshells are invertebrate eaters.

Cooters

These familiar large turtles are fond of basking. They are strong swimmers with webbed hind feet. They are generally large turtles that are some of the most common turtles seen on rivers and streams.

Texas has two species of cooter – the Missouri River cooter is known from large waterways with moderate current and abundant vegetation in Gray and Oldham counties. They are dark turtles with intricate yellow patterns on both shell and body. Texas River cooters are also known as Texas sliders and are found in Colorado, Brazos, Guadalupe and San Antonio River drainages of central Texas. They are green with yellow markings that fade with age.

Cooters are primarily herbivorous although Texas River cooters are carnivorous, feeding on invertebrates and fish, as young. Missouri River cooters may also consume crayfish, tadpoles and small fish.

Painted Turtles

These familiar turtles are widespread and nearly continent-wide, ranging from Mexico to Canada. Two species, the Western painted turtle and the Southern painted turtle are known from Texas, with the Western painted turtle having a limited distribution in west Texas and the Southern painted turtle being found only in the Caddo Lake region of Texas. These turtles are not widespread in Texas.

The Western painted turtle has a smooth upper shell and olive to near black shell with irregular yellow lines and a reddish orange outer edge. Southern painted turtles are noted by a red, yellow and orange line running the length of the shell. Both subspecies are omnivorous, eating progressively more vegetable matter as they age.

Snapping Turtles

Generally large and mostly carnivorous, these turtles are noted for their powerful bite. They have a reputation for being aggressive (only if picked up), but in most cases they will retreat when threatened. These turtles cannot pull their heads entirely into their shell. Two species are found in Texas from two distinct genera.

The Common snapping turtle is found throughout Texas except from the Trans Pecos and the south Texas brushlands. It inhabits lakes and streams with lots of plants and is known by a large keel that flattens with age, large head and blunt, protruding snout. The Alligator snapping turtle is found in the Trinity and Sabine River watersheds and is found close to large water bodies when found in stable populations. This state-listed threatened species is distinguished by its tail and its three rows of raised plates on the shell.

Both species are carnivorous, eating fish, ducklings and carrion. Alligator snapping turtles are also noted as heavy plant eaters.

Mud and Musk Turtles

Mud turtles are small, generally reaching about 5 inches. These turtles may live 30 to 50 years, and are generally considered to mature late. They have fleshy barbells on the chin and are capable of secreting a musky smell if threatened.

These turtles have hinged lower shells that will work independently allowing them to close access to their head, limbs and tail.

Three species of mud turtle and two species of musk turtle are known from Texas. The Chihuahuan Mud Turtle is very limited, known only from Presidio County in Texas. The Yellow mud turtle is found statewide, though rare in the eastern 1/3 of the state. It is olive colored with yellow areas on its throat, head and neck. The Eastern mud turtle is found from the Pineywoods to the eastern edge of the Hill Country. A small, dark brown to olive turtle it has a spotted head but no stripes. Mud turtles feed on tadpoles, insects, worms and small mollusks as well as plants and decaying matter.

The Razorback musk turtle is found in slow moving streams and swamps of the eastern third of Texas. It has a high triangular keel when viewed from the front. The Common musk turtle is known from mud bottomed lakes, ponds and swamps in the eastern part of the state except from the rolling plains and south Texas brushland. The steeply peaked shell and two light stripes on the side of the head help identify this turtle.

Musk turtles are omnivorous, eating snails, insects, crustaceans, clams, amphibians and plants.

Other Testudines

Texas Diamondback Terrapin

Occurring from the Sabine River to Corpus Christi, the Texas diamondback terrapin shows a brackish to salt water preference. Found in estuaries, tidal creeks and saltwater marshes, sometimes with salinity approaching that of the ocean, in Texas this terrapin can be found from Orange to Nueces County, seldom more than two counties from the coast.

A 4- to 9-inch terrapin with a dark shell, diamond shaped scutes and strongly webbed feet, are characteristic of this animal. Diamondback terrapins serve as an ecological indicator species in the Gulf of Mexico.

The males will reach maturity in about three years, but females don’t mature until six years. Terrapins can live up to about 40 years.

Crabs, shrimp, bivalves, fish and insects are the principal diet of the Texas diamondback terrapin.

Texas Tortoise

Texas is the northern end of this state-listed threatened tortoise range, with much of their distribution being in the Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Coahuila and Nuevo Leon. This tortoise is a terrestrial animal, found in dry scrub and grasslands.

The Texas tortoise has a yellowish-orange shell with cylindrical columnar hind legs. It will grow to have a shell length of about 8.5 inches.

Primarily vegetarian, some captive specimens have been known to eat meat at times. They feed heavily on the fruit of prickly pear and other succulent plants.

What's in the Future for Turtles?

Between our desire for homes, roads and hotels along waterways where turtles come to lay their eggs, our desire to keep these beautiful creatures as pets, and our appetite for turtle meat, pressures on turtles are constant. Adding the impact of fishing without effective turtle exclusion devices, and these threats increase. Effective management and education can help these animals to survive.

What Can I Do?

By far the greatest threat to turtles comes from habitat destruction. How many people, when looking out over a swamp, will see a valuable natural resource critical to wildlife? How many see a muddy stream and think of wildlife habitat? Dredging, channeling and altering the course of rivers can permanently remove needed habitat for turtles. Draining swamps, converting to agriculture, water pollution and other human activities in and around water can permanently displace turtle populations. Building along stream banks often paves over or alters critical nesting sites.

Needless shooting of turtles that are simply left to rot is a waste of this valuable resource. Turtles are often wrongfully blamed for depleting fish populations. Taking the life of a non-game animal for target practice or from misguided zeal to protect fishing grounds does not demonstrate good outdoor ethics.

Taking an animal home as a “souvenir” of your visit to turtle habitat often results in a “pet” that meets a slow demise through neglect or ignorance. While often promoted as good pets, turtles, like any other animal, require attention and care. While it is legal to keep turtles as pets in Texas, check regulations to ensure that you remain within the legal framework. They can be found at www.tpwd.state.tx.us/business/permits/land/wildlife/media/nongame_regulations_faqs.doc. This page will also give you information on collecting animals commercially which is regulated in Texas.

Many turtles meet an untimely demise while trying to move across lanes of traffic as they move between waters. Seeing a turtle trying to cross the road is an increasingly common occurrence, especially during nesting seasons. Helping the turtle cross the road is the humane thing to do and might even save the animal’s life. Relocating it to a supposed “better home” can be detrimental to the animal’s future. Turtles, like other animals, have established home ranges and are likely to leave the “paradise” you found and try to return home. This is likely a death sentence for the turtle. Traveling until exhausted while looking for familiar grounds, and trying to avoid additional threats, they are likely to cross several roads and get crushed.

Creating Habitat for Turtles

Gardening for wildlife is becoming a growing hobby in Texas, with many of your neighbors and friends considering the needs of birds, butterflies, squirrels, and even toads in their landscaping decisions. Why not consider a turtle habitat as a portion of your backyard habitat? When you install your pond, consider using mud or sand as a substrate for at least part of the area. Install plants that will be used by the turtle both as shelter and as food resources. Be careful to add a gently sloping entrance / exit from the pond. Sand and soft soil to a depth of several inches should be available near the pond for egg laying. Rocks, logs and other basking surfaces, with easy access to the water should be available.

Resist the temptation to go out and “adopt” a turtle to move to your habitat. If the conditions are right, the turtles will find and use habitat you’ve created. Become a member of a local herpetological society, where you can learn more about turtles and tortoises; often these societies help place unwanted turtles and other reptiles in new homes with informed people.

Additional Information

This introduction to turtles can serve as a quick summary of Texas turtles. For more detailed information:

Books:

- Dixon, James R. 2000. “Amphibians and Reptiles of Texas.” Texas A&M University Press. College Station

Websites:

- www.texasturtles.org Biology, conservation, ecology and natural history of Texas turtles.

- www.zo.utexas.edu/research/txherps/turtles/ UT range and diagnostic features of Texas turtles

- www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/species/#reptiles fact sheets on some Texas reptiles

- http://herpcenter.ipfw.edu/index.htm?http://herpcenter.ipfw.edu/outreach/accounts/reptiles/turtles/ Center for Reptile and Amphibian Conservation and Management.

Historical and Current Assessment of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department's

Private Lands Assistance Program

By Linda Campbell

Since the 1930’s Texas Parks and Wildlife Department biologists have provided habitat management assistance to landowners. In the early years, work consisted of collecting data for hunting/fishing regulations, trapping and transporting wildlife, population studies, wildlife research, and vegetation surveys.

During the period 1950 through 1973, the increasing economic value of hunting, particularly deer hunting, lead to increasing requests for landowner assistance. Personal relationships formed and landowners began to seek guidance from biologists. Requests for assistance began on large ranches in south Texas. As it became more difficult to make a living from livestock alone, landowners sought to diversify income by selling hunting opportunities.

More landowners began to ask for advice on improving wildlife resources on their land. Soon, White-tailed deer and quality game management became the driving force in landowner requests for assistance. As requests for assistance increased in south and west Texas, field biologists saw their workload changing as they sought to respond to requests for landowner assistance separate from their traditional regulatory duties. They began to document requests for assistance to private landowners and eventually shared these changes in workload with leaders in Austin.

In 1973, as the demand for assistance continued to grow, Robert Kemp, Director of Wildlife and Fisheries proposed to implement a private landowner assistance program. Five technical guidance biologist positions were created, along with a proposal to implement a technical guidance program designed to provide landowner assistance was presented to the TPWD Commission. The Commission approved the program in 1973. Under the leadership of the first five technical guidance biologists, private lands managed according to a wildlife management plan developed with TPWD assistance, averaged about 1.5 million acres during the period 1973 through 1988.

The first technical guidance biologists were experienced field people with strong ties to their communities and solid relationships with the landowners they assisted. They were recognized as big supporters of the technical guidance program and showed a strong belief in one-on-one assistance to landowners. They became the model for self-motivated employees focused on getting people interested in wildlife management. Each developed a unique style of working with landowners to “sell” quality habitat management by addressing the landowner’s primary interests, in most cases, game management.

During the period 1988 through 1991, five additional technical guidance biologists were hired, bringing the total to 10. In 1992, as the demand for assistance continued to increase throughout the state, Wildlife Division managers made the decision to assign the responsibility of providing assistance to landowners to all field biologists as part of their jobs. With more staff assistance, the acreage managed under written wildlife management plans and recommendations more than doubled from 1992 to1994 (2.5 to over 5 million).

The importance of working with private landowners to accomplish the agency’s mission of wildlife conservation was clearly recognized with the creation of the Private Lands Advisory Board (PLAB) in 1993. The PLAB was created to advise the Department and Commission on matters of importance to private landowners. The PLAB consists of private landowners appointed by the Chairman of the Commission. The members serve as a sounding board for private lands issues of concern to TPWD and are asked to examine issues and prepare responses on specific charges given to them by the Commission Chairman.

The mid-1990’s was a particularly challenging period for wildlife conservation in Texas, particularly with regard to endangered species issues. Conflicts arose between landowners and the government agencies charged with conserving rare species. Many landowners expressed mistrust of the government in general and lack of support for rare species conservation in particular. Clearly, a new approach to private lands conservation was needed. Discussions throughout the nation began to center around the concept of providing incentives for private landowners to manage habitat benefitting rare species, while also removing disincentives inherent in the laws and policies of that time.

In 1997, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department piloted the first Landowner Incentive Program with financial support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). The first LIP program was designed to reverse the top down regulatory approach to rare species conservation and replace it with a voluntary program that provides financial and technical assistance to landowners to help achieve their overall conservation goals for the land, including habitat-based work benefiting rare species. For many landowners, this voluntary, incentive-based approach was all that was needed to encourage participation in the conservation of rare species on private land throughout the state. In 2002, LIP became a national program administered by the USFWS, offering the same incentive-based approach to all states.

As a result of the endangered species controversies of the mid-1990’s, Section 12.0251 was added to the Parks and Wildlife Code in 1995. This statute mandated that information and species data used to develop a wildlife management plan for private landowners was confidential and could not be released without the written permission of the landowner. This law provided the assurance many landowners needed to feel comfortable requesting technical assistance and inviting Texas Parks and Wildlife biologists on their land.

Another key law (H.B. 1358), passed in 1995, implemented a constitutional change by amending the Texas Tax Code to allow wildlife management as an agricultural use that qualifies the land for agricultural appraisal. Commonly referred to as the Open Space Tax Valuation for Wildlife Management, this law allowed landowners to declare wildlife management as their primary agricultural use, providing added flexibility for land managers throughout the state. The result was an increase in landowners managing primarily for wildlife and an accompanying increase in landowner requests for assistance.

As approaches to private lands conservation changed from regulatory to incentive-based, the Private Lands Advisory Board led the way in creation of the Lone Star Land Steward Awards program in 1996. This program, now in its 13th year, recognizes landowners in each of the 10 ecoregions and one overall statewide steward that have shown accomplishment and commitment to excellent resource management and stewardship on their lands. These landowners are held up as models and the awards program itself serves as a venue for TPWD to highlight the important role private landowners play in conserving the wildlife resources of Texas.

Consistent with the Department’s incentive-based approach to private lands conservation, the Managed Lands Deer Program (MLDP) was implemented in 1999. Landowners choosing to participate in this program were afforded maximum harvest flexibility in exchange for providing harvest records and accomplishing management actions identified in their wildlife management plan. This has been a highly successful program and has greatly increased demand for private lands assistance.

The trend of land fragmentation due to increasing numbers of small acreage properties continued to tax the ability of TPWD biologists to keep pace with small acreage landowners seeking assistance. Biologists throughout the state have worked to promote the formation of landowner associations, providing an opportunity to address wildlife conservation on a landscape scale while also providing staff an efficient way to deliver conservation information and services.

By the year 2000, TPWD reported 8.3 million acres being managed under a wildlife management plan developed with TPWD assistance. In this year, the Legislature authorized funding for 10 additional field positions to be used to provide additional assistance to landowners. The Wildlife Division’s decision to assign landowner assistance as part of the job duties for each field biologist grew the workforce available to meet the demand for landowner assistance. From August 2000 through November 2008, the number of active wildlife management plans and the acres under wildlife management plan increased from 2,272 plans and 8.3 million acres to 5,785 plans and 21.5 million acres. The acreage being managed for wildlife by wildlife management associations increased from 979,597 acres in 1999 to 2.6 million currently.

It is clear that efforts to reach out to private land managers have paid off in the numbers of landowners now actively managing for sustainable wildlife populations. As we look to the future, it is also clear that the one-on-one, incentive-based approach to private lands assistance is becoming increasingly more difficult to sustain within the constraints of current funding and staff allocations. As one Private Lands Advisory Board member put it, “the program is a victim of its own success.” Field biologists are challenged to meet the growing demand for services from new landowners buying land primarily for recreation while also providing adequate assistance to current cooperators implementing habitat improvements. They continue to devise innovative ways of working more effectively with groups of landowners while providing follow-up assistance to those most interested in accomplishing habitat improvement. The accomplishments of dedicated field staff cannot be overemphasized. Most will continue to work hard to educate, enlighten, and “sell” wildlife habitat conservation to landowners because they are wildlife professionals and the message is important to them personally. TPWD will continue to seek ways to support current staff with adequate salaries, vehicles, and equipment while adding to their ranks as we strive to meet the growing demand for landowner services. And in a state that is 96 percent privately owned or managed, our work with private landowners is our only hope to conserve the habitats and wildlife resources of Texas.

Linda Campbell is the TPWD Private Lands and Public Hunting Program Director

The Benefits of

Backyard Bugging

By Mike Quinn

A few weeks ago I bought a new (to me) camera body that allows me to once again use my close-up lenses left over from the film era. Since then, I've been shooting backyard bugs. Here's a selection of some of what I'm seeing:

Quinn's Backyard Bugs

South Austin, Travis County, Texas

www.texasento.net/backyard.htm

One of the great advantages to shooting "out back" is that one has a very good chance of associating immature insects with their adult forms, which are the easiest stage to ID. Other than pest species and caterpillars, most immature insects are not well known. Thus, documenting various immature states is an important area where very significant contributions can be made to our entomological knowledge.

In a larger, more diverse area than the typical city lot, the immature and adult insects present are likely more diverse, complicating the association of various stages.

Also, one generally spends more time at home than away which makes seeing a species’ instars easier. Most insects molt five times during their larval stage (between egg and pupa or adult). The stage between larval molts is referred to as an “instar,” and most insects have five instars.

Variation among instars within a species can be significant. This is one of the complicating factors in identifying immatures. Most books don’t have room for photos of all the adult insects of a group or region let alone five times as many immatures!

Many insects only have one generation per year which generally matures from egg to adult in about a month. If one makes two visits to a park, refuge or nature center in a month, they would only potentially catch a few snapshots of a species’ life history versus being at home, where one might watch (and record) the whole parade of a species’ march through the various larval molts.

Immature insects are occasionally more boldly patterned if not more beautiful than their adult stage. One might not be too surprised about this phenomenon with an insect that undergoes “complete metamorphosis”, i.e. an insect with a pupal stage. For instance, numerous colorful caterpillars turn into rather drab adult moths.

However, even insects that undergo “gradual metamorphosis” such as grasshoppers can have a juvenile stage that eclipses the adult in terms of gaudy coloration. The Aztec Spur-throat (Aidemona azteca) for example as a juvenile has a front end that resembles a University of Michigan football helmet, the abdomen is a series of yellow, black and white parallel bands and the legs, especially the enlarged hind legs, are awash in orange and yellow as if on fire. The adult Aztec Spur-throat is quite cryptic by contrast. The ground color is clay toned with mostly minor markings and patches of blacks and browns. The wings are a light blue-gray. It’s as if the tie-dyed teen grew up and put on a business suit!

Immature pic shot in Jim McCulloch’s yard (Awesome!): http://bugguide.net/node/view/120443/bgimage

Adult pic shot in my side-yard: http://bugguide.net/node/view/201487/bgimage

Almost no entomologist I contacted in the past was able to associate the immature and adult images, though now that a long series of (mostly backyard) photos have been posted to BugGuide.Net, the identification of both the larvae and adults is becoming common knowledge.

Another advantage to backyard “bugging” is that one has a greater impetus to identify a backyard bug than something shot further away. We want to know more about what resides close to us than about critters at distant locales. When we go hiking down trails away from home, we tend to focus on a narrower range of critters such as birds, dragonflies or butterflies. Being in the backyard gives us an excuse to investigate critters outside of our “comfort zone” such as true bugs, beetles and/or spiders. With luck, one may develop an absolute fascination for a group of insects that one never knew they even liked previously!

Mike Quinn is a TPWD Entomologist officed at the Austin Headquarters

The Back Porch

The Back Porch

A passion for people

By John M. Davis

I'm a wildlife biologist. Therefore, I'm in the "people business". If you think those two statements contradict one another, you're not alone. However, it's true. Wildlife management is people management. Think about it. People own the habitat. People make land use decisions. People enact environmental policy. People vote. It's people that decide the fate of wildlife. So as one who loves wildlife, I'm in the people business.

Unfortunately, I feel that there are many who get into the wildlife management field without understanding that fact. It's a common misconception that one can become a wildlife biologist and be a "Grizzly Adams" type, living in the wilderness and not have to deal with people. Those days (if they ever really existed for wildlife managers) are long gone.

Today's Texas is a fragmented and urban one. In 2000, 20.8 million people lived in Texas. Of those, 17.9 million (86%) were urbanites (city dwellers). The areas of Dallas / Ft. Worth and Houston housed a whopping 47% of our entire population! By 2040, it's projected that nearly 90% of our population will live in the city with over half of the state living around Dallas / Ft. Worth or Houston. We are a state of urbanites and there is no indication that this trend will cease any time soon.

How does that relate to the seemingly endless open terrain in the rural parts of Texas you ask? Many, if not all, of the conservation issues statewide are tied to people. First, water quantity and quality issues are directly tied to our human population and the impacts of urbanization. Many folks worry about how we will provide water for all the people in Texas while still leaving some for fish and wildlife. Folks also debate the construction of new reservoirs to meet the demand for humans at the expense of bottomland hardwood habitats. Nonpoint source pollution is a term that describes chemical and physical contamination that's picked up as rain water washes over parking lots, rooftops, etc. This category of water pollution is often the most damaging to water quality in our streams and rivers and is usually directly tied to urban land uses.

Second, the large landholdings of Texas' past are being carved into numerous, smaller landholdings. A significant percentage of the landowners in Texas today are absentee landowners. They own property "out in the country" yet live in the city. Many of these new landowners are anxious to learn how to best manage property for wildlife. So as wildlife managers in Texas, we must be able to connect not only with our traditional landowners, but also with the new landowners who often bring different value systems, goals and objectives to the table with them.

These are just two examples that our human, largely urban population is having direct or indirect impacts on wildlife resources well beyond the limits of the local city. With the previously mentioned population projections, these issues aren't going to get any easier. In fact, they are likely to become even more complicated for wildlife managers.

Unfortunately, most wildlife managers aren't trained to operate in this new people-centered environment. Most of us were taught about population dynamics, habitat manipulation, and carrying capacity of the land, but today's wildlife biologist has to deal with development, public speaking, changing social values, regional planning, etc. So, like any species in a new environment, we must adapt, migrate or die. Fortunately for us, we are adapting. As of 2005, we are blessed with a guiding document called the Texas Wildlife Action Plan which was painstakingly developed over a year's time by the talent of many, very educated and passionate people. In this document, we have a vision of where to place priorities to ensure the continued existence of the wonderful wildlife in our state. The plan also emphasizes the importance of working with people. Therefore, it actively supports the Urban Wildlife Program, the Wildlife Interpretive Program, Texas Nature Trackers, Texas Master Naturalist, and Texas Wildscapes, which are a few of the programs specifically designed to meet people where they are and lead them to a better relationship with wildlife. As the Conservation Outreach Coordinator for the Wildlife Division, I am proud to be associated with all of these programs and am excited about the role each will play as we all strive to conserve our beloved species and habitats for the enjoyment of future generations.

Hopefully, I'll soon get to meet you as part of one of these programs and hear about the particular plant or animal that just lights you up (mine's the Texas Horned Lizard). Until then, take care and remember ... as wildlife enthusiasts, we're in the people business.

John is Conservation Outreach Coordinator with the Wildlife Diversity Program working out of Austin

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744