Spring 2012 A publication of the Wildlife Division—Getting Texans Involved

Pronghorn Problems in the Trans-Pecos

Pronghorn Problems in the Trans-Pecos

By Shawn Gray

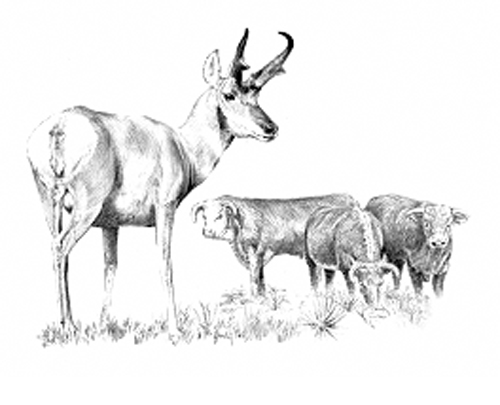

Research indicates that Trans-Pecos populations have a significant positive correlation with precipitation. For example, as annual precipitation increases populations grow and vice versa. The Trans-Pecos population burgeoned to an all-time high of more than 17,000 in 1987 with about 70% of the state's herd residing in the region. During the drought of the late 90's populations decreased to about 5,000. However, populations rebounded to about 10,000 in 2007 when normal range conditions returned. The following spring and summer would start a "perfect storm" that brought pronghorn numbers spiraling downward. Dry conditions and a late freeze in 2008 sparked a drastic decline in the Marfa Plateau. This loss was coupled with virtually no fawn recruitment in 2009 and 2010. Now the population has reached a record low since the 1940's with the region's herd only 30% of the state's total.

Numerous factors such as precipitation, habitat quantity and quality, barriers to movements, and predation influence pronghorn populations. In 2009 and 2010 when abundant rainfall replenished the range, pronghorn numbers in the Marfa Plateau did not respond. Fawn crops during summer surveys estimated only 9 fawns per 100 does in 2009 and 5 fawns per 100 does in 2010.

Autopsies during the spring and summer of 2009 revealed high levels of Haemonchus or barber pole worms-blood-sucking stomach worms. Adult barber pole worms can draw 0.1cc of blood/worm/day by attaching to the stomach wall. The levels we discovered in the autopsied pronghorn were disturbing. Most pronghorn herds have these parasites associated with them, but in much lower numbers. Because of this dilemma the Trans-Pecos Pronghorn Working Group was formed. This group, composed of landowners, researchers from the Borderlands Research Institute at Sul Ross State University (BRI-SRSU), outfitters, hunters, wildlife veterinarians, and TPWD personnel, first met in September of 2009. Plausible causes for recent declines were discussed and the working group quickly developed a plan to sample hunter-harvested pronghorn for disease surveillance.

After the 2009 season closed, we had amassed 102 samples representing 50 ranches and 1.8 million acres for analysis. Almost all samples contained Haemonchus, but the highest average were from the Marfa Plateau (777 worms/pronghorn). The samples were also low when tested for essential minerals needed for reproduction. These results were puzzling to say the least.

In 2010, 95 samples were collected during the hunting season throughout much of the same range that was sampled in 2009. Barber pole worm loads decreased by about 50%. In contrast, mineral levels increased in 2010. We will continue to monitor barber pole worms in Trans-Pecos pronghorn and will study fawn survivability during the spring of 2011 and 2012 to determine causes of fawn mortality.

Because of surpluses in the Panhandle population (which are causing increased crop depredation) and historically low numbers in some areas of the Trans-Pecos (Marfa Plateau) a restoration project was started. Donations from the Trans-Pecos Pronghorn Working Group, Dixon Water Foundation, Horizon Foundation, and West Texas Chapter of Safari Club International (SCI) were used to match TPWD Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration monies to fund the project, which is contracted to BRI-SRSU. Our objectives are to reduce Panhandle surpluses, supplement decreasing Trans-Pecos herds, monitor and evaluate success of translocations, study movements and habitat selection of relocated animals, and investigate pronghorn and Haemonchus interactions.

In February 2011, 200 pronghorn were moved from the northwest Panhandle to the Marfa Plateau. Eighty of these pronghorn were radio-collared for intensive surveillance. Samples were collected from each pronghorn for disease tests. Previous testing showed that Panhandle pronghorn have barber pole worms at much lower concentrations than Trans-Pecos animals. Relocated pronghorn are being monitored 3-4 times a week and will be used to compare barber pole worm concentrations in different seasons (summer and fall) and between resident pronghorn. We will also compare fawn survivability between relocated and resident pronghorn.

Our knowledge about Trans-Pecos pronghorn relative to diseases, health, movements, and habitat usage is growing but there are numerous questions that remain. We are proactively trying to answer each question in a systematic and scientific approach.

Thanks to tremendous support and teamwork from landowners, Trans-Pecos Pronghorn Working Group, TPWD Leadership, BRI-SRSU, wildlife veterinarians, local communities, Dixon Water and Horizon Foundations, and West Texas Chapter of SCI, we continue to learn how to conserve our Trans-Pecos pronghorn resource in the midst of baffling declines.

Shawn is Mule Deer and Pronghorn Program Leader working out of Alpine.

Understanding the Plants

A Landowner's First Step in Wildlife Management

By Philip Dickerson

As wildlife resources become increasingly important to landowners for economic and aesthetic reasons, their first step should be is to learn all they can about the native vegetation on their properties. In my conversations with landowners and managers, I refer to this as building the "foundation" from which good management decisions can be made. In today's modern high tech, fast paced world there are many perceived shortcuts (breeder pens, high fences, supplemental feeding and culling) to improving our complex natural systems. Managing wildlife in the Trans-Pecos requires patience, hard work and knowledge of the animals and native vegetation.

There are resource professionals (TPWD, NRCS, AgriLife Extension Service and Universities) available to assist landowners with this technical guidance throughout the region. Additionally, managers should seek out good field guides on grasses, forbs and woody plants to help with this important aspect of becoming a good habitat manager.

This may sound like a lot of work but it can also be a lot of fun. In the beginning it may seem like information overload but the work will pay off in the end. I would suggest taking a camera with you, photographing the plants as you go, and build your own plant inventory for your ranch. It's not only important to know "what it is" but "what value" these plants have to the different animal species. For example, several species of native grasses produce abundant seeds that will be utilized by many species of birds in addition to providing nesting cover. Many of the woody plants that fall into the "shrub" category produce a seed or fruit that becomes a food source for different animals. The terminal ends (new growth) of the stems are often browsed on by deer, elk and bighorn sheep. The point is that many of our native plants provide multiple functions (food, nesting and cover requirements) for wildlife. Understanding the quality and quantity of the native vegetation is vital to developing a management program. One of my goals when working with any landowner is to provide enough of this information so that the owners will begin to view their native grasses, shrubs and trees with a new perspective - how it relates to wildlife value. With this understanding I hope that as they drive across the ranch they begin to piece together the different habitats that exist and begin to recognize those special wildlife values. This understanding is also critically important so that future management decisions will enhance the habitat and not be detrimental. The time spent on the front end of any management program will provide a greater appreciation later. I would encourage all landowners to take the time to build a good "foundation" of native plant knowledge and pass it on.

The Trans-Pecos District encompasses 16 counties. The Trans-Pecos landscape is blessed with more species of shrubs, grasses and forbs than any other region in the state. Landowners seeking help with wildlife management may contact the Alpine District Office at 432-837-2051 or use the Texas Parks and Wildlife website and click on the Land and Water tab, then under the Land menu, click on Find a Biologist.

Philip is a technical guidance biologist with TPWD out of Midland, TX.

Mountain Lions in Texas

By Jonah Evans

Back when the majority of landowners were ranchers and many livelihoods depended on livestock production, it is understandable that large carnivores were difficult to tolerate. However, as the demographics of Texas shifted from rural to urban and as fewer landowners relied on their property for profit, efforts to eradicate predators subsided. Mountain lions (also called puma, panther, and cougar) managed to survive the era of persecution primarily in remote areas of the western and southern parts of the state. That they were able to persist while the other large carnivores did not is testament in part to their stealth and incredible adaptability.

Mountain lions are specialized carnivores, but can eat a surprising variety of prey. While they tend to specialize on deer, they also eat peccary, feral pigs, raccoons, porcupines, coyotes, and anything else they can. This adaptability enables them to have the largest distribution of any land mammal in the western hemisphere. They are found from Canada to southern Chile and Argentina and are able to live in deserts, mountains, jungles, and grasslands. Despite this impressive distribution, they currently inhabit a fraction of their original range. Once found across all of the lower 48 states, now generally only the western third of the U.S. contains viable mountain lion populations.

In the western U.S., large mountainous tracts of public land and regulated hunting have contributed to fairly stable mountain lion populations. Today, hunting is permitted in every state where a viable lion population exists except California, where a public referendum prohibited all mountain lion harvest.

Although mountain lions still subsist in west and south Texas, the actual status of Texas' lion populations is not well known. Surveys for mountain lions are exceedingly difficult; attempting to count one of America's most elusive carnivores as it roams hundreds of square miles in remote deserts and mountains is no easy task. Small research budgets and limited access to private lands further complicate efforts to estimate mountain lion numbers. Some western states use mandatory harvest reporting to roughly estimate populations. In Texas, a few hunters and trappers voluntarily submit harvest reports, but most do not, making the number of hunted lions almost a complete mystery.

Recent genetic studies suggest that Texas has 2 distinct populations of mountain lions: a more robust west Texas population, and a possibly declining south Texas population. Genetic flow between these populations appears to be very limited. This may be an indication that very few lions exist between these populations.

While the core population centers are in west and south Texas, mountain lions periodically make their way into more the populated central and eastern portions of the state. These lions rarely threaten humans or livestock, but sightings often frighten those not accustomed to having a large predator in their back yards.

Sighting a mountain lion in the wild is a rare event that few people get to experience. TPWD receives numerous reports of lion sightings each week, but many are difficult or impossible to confirm. A large number of the callers report seeing a "black panther", which leaves biologists in the awkward position of explaining that there has never been a proven case of a melanistic (black form) of a mountain lion. Any large black cats seen in Texas could only be escaped melanistic leopards or jaguars. However, it is unlikely that the large number of sightings of "black panthers" in Texas signifies a pandemic of escaped exotic felines. While the natural coat of an adult mountain lion is a rich tan color, they can appear very dark when in shadows or in low light. Possibly this accounts for the majority of Texas's "black panthers". Many dogs are also mistaken as mountain lions at a distance or in poor light. In contrast with dogs, mountain lions have a long body, a very long drooping tail, and a small head and ears.

While mountain lions can be dangerous and attacks on people do happen, they are extremely rare. There are just 20 confirmed fatal lion attacks on humans from 1890-2011. Eleven of these happened since 1979. Compare this to the 538 human deaths from domestic dogs from 1979-2011. If you do have a chance encounter with a mountain lion, and it displays aggressive behavior (stalking, crouching, etc.) make an effort to appear large and unafraid. If you are with other people, gather in a group. Put all children behind you. Do not run. Wave your arms, yell, and throw objects. Pick up a stick or other improvised weapon and if attacked, fight back. The victims of most fatal mountain lion attacks are children, so if you're hiking in lion country be sure to keep kids in sight. Many other lion attack victims are runners. Avoid running in lion country, especially at dawn and dusk.

Despite the potential danger mountain lions present to people and livestock, public perception in Texas is relatively high. A recent survey found that 84% of respondents believed mountain lions were an essential part of nature and that 74% believed efforts should be made to ensure their survival in Texas. The high support for mountain lions signifies just how much Texas has changed since the early years of predator eradication.

With the strong public perception of mountain lions in Texas, it is increasingly important that biologists have reliable population data. Making effective efforts to ensure the continued survival of mountain lions in Texas requires accurate information and TPWD is currently investigating an innovative fecal genetic technique and footprint identification technique that may help. If successful, these methods could finally provide an efficient and effective way to monitor one Texas' most elusive carnivores.

Jonah is a Diversity Biologist working in the Alpine area.

2011 Saw Changes to the Wildlife Diversity Program at TPWD

By Mark Klym

John Davis became the Program Director after serving in the role as Acting Program Director since 2010. Previous to this, John has served as Program Director for the Conservation and Outreach Program, an Urban Biologist in the Dallas Fort Worth area and a field researcher studying endangered songbirds. John is committed to passing on the passion he has for wildlife to as many people as possible, and to helping other biologists convey this passion as well.

Richard Heilbrun is the new Conservation Outreach Coordinator for the Wildlife Diversity Program. Richard has more than 11 years experience providing technical guidance to landowners, conservation organizations, urban planners and developers. Richard has served as a Wildlife Biologist for the Victoria area, an Urban Biologist in the San Antonio area and an intern at Elephant Mountain Wildlife Management Area. He has also worked for the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute and the Welder Wildlife Foundation.

Wendy Connally is the new Team Leader for several groups including the Texas Conservation Action Plan, the Permits Program and the Rare Species Program. Wendy has more than 20 years experience in rare species work including work with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Lower Colorado River Authority, Bureau of Land Management, and the Nature Conservancy in both Texas and Washington State.

Michelle Haggerty has added to her duties as coordinator of the award winning Master Naturalist program which she has overseen since 1999. She has taken on the oversight of the Outreach Programs in the Wildlife Diversity Program. Prior to her work with the Master Naturalists, Michelle has worked with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Natural Heritage Program and the Michigan State University Extension Program.

The Desert Bighorn Sheep Restoration Effort: A Work in Progress

By Froylan Hernandez

Protective measures were taken as early as 1903 with the prohibition of bighorn hunting and later with the establishment of the Sierra Diablo WMA (1945), a sanctuary for the few remaining bighorns. A cooperative agreement in 1954 between the Arizona Game and Fish Commission; Boone and Crockett Club; Texas Game, Fish and Oyster Commission; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; and Wildlife Management Institute marked the beginning of the restoration efforts in Texas. These efforts focused primarily on captive propagation. The first propagation facility was constructed on the Black Gap WMA and stocked with 16 desert bighorn sheep from Arizona in 1959. Additional facilities were constructed at the Sierra Diablo WMA in 1970 and 1983, and Chilicote Ranch in 1977.

Today, desert bighorns are coming back to their historic mountain ranges. Greatly in part to decades of work by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, various state agencies including Arizona, Utah, and Nevada, as well as wildlife conservation groups such as Texas Bighorn Society, Wild Sheep Foundation, and Dallas Safari Club. Of equal importance have been the many private landowners and individuals committed to the restoration and management of desert bighorn sheep.

Surveys resulted in nearly 1,100 sheep for Texas in September 2011, up from 822 in 2006 and 352 in 2002. Currently, restoration efforts have resulted in an estimated 1300 bighorns occupying about half of their historic mountain ranges.

Since 1959, 596 desert bighorns have been restored to 8 mountain ranges in the Trans-Pecos. Of these, 146 have been from out-of-state sources including, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and Baja California, Mexico. The remaining 450 have been in-state transplants all occurring after 1971. Three major capture and transplants have occurred since 1971. The first was conducted in December 2000 when 45 bighorns (23 M, 22 F) were moved from Elephant Mountain Wildlife Management Area to Black Gap Wildlife Management Area.

The second in December 2010 when 46 bighorns (12 M, 34 F) were transplanted from Elephant Mountain WMA to the Bofecillos Mountains of Big Bend Ranch State Park. Up until this point, the Bofecillos Mountains and surrounding ranges had been unoccupied by desert bighorn for over 50 yrs.

The third, took place in December 2011. It marked the largest in-state capture and transplant in Texas bighorn restoration history. A total of 95 bighorns (19 M, 76 F) were captured from the Beach, Baylor and Sierra Diablo Mountains located north of Van Horn, TX. All bighorns were transplanted to the Bofecillos Mountains of Big Bend Ranch State Park over 160 miles to the southwest.

Of the 141 bighorns that have been transplanted since December 2010, almost 80 have been fitted with radio-collars with transmitters that enable the monitoring of the bighorns. Monitoring the bighorn permitted evaluation of the success of the transplant and provides data that will aid in our understanding of the bighorn and its management in Texas.

Preliminary observations indicate some bighorns have made movements almost 15 miles to the north of the release site. But movements have not stopped there. Several collared bighorns have ventured south of the border, crossing the Rio Grande and making use of bighorn habitat on the Mexico side. Some of these bighorns have journeyed over 10 miles from the release site into Mexico. It appears a few bighorns travel back and forth, which will allow the identification of wildlife travel corridors.

Though there have been several milestones accomplished and these initial results are interesting, there is still plenty of work ahead and the future of the Texas bighorn restoration effort is a work in progress.

Froylan is the Desert Bighorn Sheep coordinator working out of Alpine.

Fishes of the Texas Desert

By Stephanie Shelton and Gary Garrett

Below are some of our interesting species and issues:

Rio Grande Silvery Minnow

If you are fortunate enough to see a Rio Grande silvery minnow (Hybognathus amarus) swimming in the waters of the Texas Big Bend region, it is due to a coordinated effort of Texas Parks & Wildlife, US Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service and University of Texas-Pan American. To date, over one million fish have been released into the Rio Grande, in and adjacent to Big Bend National Park and Big Bend Ranch State Park, in an experimental effort to restore this once common minnow of the Rio Grande.

The Rio Grande silvery minnow was extirpated from Texas in the 1960s with the only remaining population located near Albuquerque, New Mexico. With approximately six percent of its historic range still intact, this species was very near extinction and was listed as endangered on July 20, 1994.

It is typically reasoned that the decline in this minnow's abundance and range was due to decreased water quality and quantity. Recent studies have also suggested that changes in the geomorphology of the Rio Grande along with reduction of drift zones which facilitated egg development are another cause. Presently, connectivity, streamflow, and habitat and water quality issues are being addressed with the goal of improving this portion of the watershed.

Pecos Pupfish

In the Pecos River basin of Texas and New Mexico, there are saline waters that are home to the Pecos pupfish (Cyprinodon pecosensis). In Texas, the only remaining location of this species occurs in Salt Creek, Reeves County, Texas. In New Mexico there are still multiple locations that exist.

The Pecos pupfish was on the candidate species list for some time but it was removed in 2001. It was determined that a Conservation Agreement could be as, if not more, effective in reducing threats to its populations than listing it under the Endangered Species Act. The Conservation Agreement was designed to facilitate and encourage conservation and stewardship by private landowners and provided assurances of no negative repercussions if the fish were to eventually be federally listed. Although not mentioned as a reason for removal from the candidate list, in Texas it signified the good faith effort of keeping this species "common" in light of any possible tensions between landowners and government entities.

The Texas population differs genetically from the New Mexico populations and is the most susceptible to extinction due to introgression by the sheepshead minnow (Cyprinodon egarding). Other stressors like the quality of their habitat (groundwater depletion, drought, and water quality degradation), golden alga toxic blooms, and geographic variations add further pressure to an already small population.

Devils River Minnow

The Devil's River minnow (Dionda diaboli) is found only in a unique area where three very special ecoregions overlap. These are the Edwards Plateau, Southern Texas Plains and the Chihuahuan Desert. Spring fed streams and rivers of this area that have gravelly or riverine cobble substrates, channels, and rapid water flow are the preferred habitat for the Devils River minnow. Today this state and federally threatened fish species is only found in the Devils River, San Felipe Creek, and Pinto Creek - only a small portion of its original range from Rio Grande tributaries in this part of Texas and northern Mexico.

Presently, the biggest threats to this species are water quality and quantity degradation as well as non-native species. These factors have been exacerbated by dam construction, causing fragmentation and habitat deterioration, as well as continuing drought conditions.

Efforts are being made to conduct further research on the life history of this fish. Additional information on its feeding patterns, reproductive behaviors, and life span may help in its recovery. This information coupled with watershed conservation and good land stewardship will help to improve and maintain habitat quality for not only D. diaboli but also all the other inhabitants of the region.

Rio Grande chub

The Rio Grande chub (Gila egardi) is found in Little Aguja Creek in the Davis Mountains, Jeff Davis County, Texas. Elsewhere, it is found in limited portions of the Rio Grande, Pecos, and Canadian basins of New Mexico and the Rio Grande and Pecos basins of southern Colorado. Presently, it is considered a sensitive species according to the USFS Region II and has special status among other agencies.

The preferred habitat of the Rio Grande chub is found in fast-flowing, cool, clear, headwaters of creeks and smaller rivers that exhibit sandy to gravelly substrates. Areas that include pools, undercut banks, and overhanging vegetation and macrophytes are where this species tends to congregate. At this time, it is suggested that this species is no longer found in the mainstem of the Rio Grande but now only in tributaries.

Threats to this species include water flow issues and fragmentation due to water diversion structures such as dams and reservoirs, non-native, invasive species have increased competition as well has predation on the chub. Finally, habitat alteration and degradation have changed the structure of the riparian areas, decreasing the availability of preferred habitat for the species.

Stephanie is Science and Policy Coordinator for Inland Fisheries working out of Austin. Gary is the director of the Watershed Policy and Management Program working out of Austin

San Solomon Springs Cienega

By Mark Lockwood

The state park is the primary conservation area for the endangered Comanche Springs Pupfish (Cyprinodon elegans). This fish was also found at Fort Stockton in Comanche Springs before that spring ceased flowing in 1961. Surveys at San Solomon Spring for this small fish in the late 1960s raised concerns about the continued survival of the species. This resulted in the construction of a refuge for the species in 1975. This concrete refugium also provided habitat for the endangered Pecos gambusia (Gambusia nobilis) and the three rare invertebrates: Phantom Spring snail (Tryonia cheatumi), diminutive amphipod (Gammarus hyalleloides), and Phantom Lake cave snail (Cochliopa texana). This small refuge played a very important role in the continued existence of these organisms for nearly 20 years. In the early 1990s a multi-partner project was started within the state park to expand the amount of habitat available and help conservation of these organisms as well as San Solomon Spring itself. The completion of the San Solomon Cienega in 1994 provided a larger, more natural wetland.

In addition to constructing the pool, the CCC also built a motor court and other buildings. The 1975 refuge was built to encircle two sides of the motor court and by 2006 the concrete bottom was severely cracked and leaking water. This was damaging the adobe walls of the courts and TPWD started looking for solutions that would protect both the fish and the historic building. The only viable solution was to move the water farther away from the building and grade the surface to keep water away from the walls. The potential to build more high-quality habitat for the fish similar to the San Solomon Cienega lead to a partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). During 2008 the plan for construction of a new cienega was developed through a Section 6 grant from the USFWS. This allowed construction to start in 2009. In addition to the USFWS other groups were very important to the completion of the project, including the Reeves Country Water District, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), Sul Ross State University, and the Tierra Grande Master Naturalists.

The planning process was the easy part of the project and construction started in the summer of 2009. The Balmorhea TxDOT office was a major contributor to the construction of the new cienega by providing man-power and equipment for the _egarding of the surface and construction of the wetland. This process turned out to be more difficult than originally anticipated because of the incredible gravel bar that was just under the surface. Despite difficulty, the Clark Hubbs Cienega was completed and water was flowing through the wetland by spring 2010. This phase of the project is just part of the story, the fantastic capacity of these desert fishes to occupy new habitat was something to see.

As part of the construction process a population of the endangered fish were moved from the old concrete refuge into the main portion of the wetland which was maintained using spring water. However due to fish-eating birds and other factors the number of fish present by the time the water was flowing in April 2010 seemed to be low. The response to the stabilized environment brought about by the constantly flowing water was nothing short of astounding. Within two weeks there were hundreds, if not thousands, of juvenile fish in the new system. Chad Hargrave from Sam Houston State University and his students began studying the productivity of the new cienega and collected data that support what was readily apparent. There were excellent numbers of Comanche Springs pupfish by mid-summer and that trend has continued. The same is true for the other species of conservation concern. We have also learned that there are productivity differences between the two cienegas and are looking for ways to increase the populations of these fish in the San Solomon Cienega based on these data.

There have been several benefits to this project, both to the park and the fish. Despite some of the difficulties in constructing the wetland, it is functioning better than anticipated as a refuge for the aquatic organisms associated with San Solomon Spring. We have taken a big step forward in the protection of the Comanche Springs Pupfish in particular and we hope to be able to build on that momentum. The success of the design of the wetlands has also removed a danger to the historic CCC motor court and added to the overall aesthetics of the park.

Mark is a Natural Resource Specialist with the Parks Division working out of Fort Davis.

Saltcedar Beetle and The Rio Grande

By Kristi Drake

Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.), native to Central Asia and the eastern Mediterranean area, was introduced into the United States in the late 1800's as an ornamental and for use in erosion control. In 1920, saltcedars started to spread rapidly and today they infest some 2 million acres of important riparian habitat that is vital to fish and wildlife. In Texas, the largest infestation is along the Rio Grande, also known as the "Forgotten River" that stretches 285 miles from El Paso to Lajitas, TX.

Saltcedars are drying up desert springs and arroyos, displacing native plant communities, driving out native cottonwoods and willows, and degrading fish and wildlife habitat. They increase soil salinity and wildfire frequency, lower water tables and reduce the recreational value of parks and natural areas.

The reproductive strategy of saltcedar makes it extremely difficult to control. Mechanical and chemical controls require repeat applications, due to copious resprouts and reinvasion of seeds, This causes an increase in cost and damage to native plants and aquatic organisms. As a fire-adapted species, saltcedar also limits the use of prescribed fire - a less expensive management tool.

The best hope for long term, cost effective control lies with a tiny olive-green beetle: the saltcedar beetle (Diorhabda elongata). Imported from China, Crete, Tunisia, Karshi, and Uzbekistan, the vivacious beetle looks out over the sea of green saltcedar and thinks "buffet"! No bigger than a ladybug, the saltcedar beetle (both adult and larvae) feeds on the saltcedar's scale-like leaves and bark of small twigs, completely defoliating it. Overwintering under the leaf litter and soil, the beetle returns the next spring and begins to feed again. After 3 or 4 years of defoliation the saltcedar begins to die from starvation. Sound simple? Not entirely.

Research and monitoring potential biological control (bio-control) agents can take years, even decades. For the saltcedar beetle it took decades. Extensive studies of biological control agents for Tamarix started in the 1970s in Italy. Some 300 species were found to be natural enemies of saltcedar but further investigations were needed before permission was granted by USDA-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to introduce any of them (DeLoach and Knutson, 2004). The federal agency, along with advisory boards, must be certain that any introduced bio-control agent is host specific and safe for the environment.

In 1986, C. Jack DeLoach of USDA - Agricultural Research Service (ARS) along with collaborating scientist began reviewing literature and testing promising host-specific species for saltcedar overseas. Six years later, ARS was granted permission by APHIS to introduce seven species of insects into quarantine at the ARS Facility in Temple, TX for final host range testing. In 1999, the saltcedar beetle was chosen as the top candidate for the job and APHIS granted permission for the beetles to be released in secured cages. Two years later approximately 60,000 beetles were released into the open field across six western states, 500 of these being released in Texas.

The beetles did not establish in Texas. ARS discovered that in order for the beetles to survive, day length/diapause characteristics needed to match that of their native habitat. The saltcedar beetles that had survived in other states were collected north of the 38th parallel (China/Chilik, Fukang, Kazakhstan) and required a summer day length period of at least 14 hours 45 minutes (DeLoach and Knutson, 2004). Texas needed a beetle that was adapted to a day length period of less than 11 hours to avoid premature diapause (overwintering). The search began and by 2005 beetles from Uzbekistan, Crete, and Tunisia were discovered and approved for release, establishing well in central (mimicking Crete) and northern (mimicking Uzbekistan) areas of Texas.

Beetle release and establishment along the Rio Grande still had hurdles to jump. From 2003-2007, national biological control meetings and an international symposium were organized between Mexico and the U.S. to address the concerns of Mexican scientists about releasing beetles along the international boundary (DeLoach et. al., 2009). Their uncertainty was based on the concern that the beetles would damage the Athel (Tamarix aphylla), a close relative of saltcedar valued for its shade and wind breaking ability in Mexico. Field surveys showed that saltcedar beetles would feed slightly on athel, but would cause no more than minor damage to them.

By June of 2007, the Mexican officials approved the release of saltcedar beetles along the U.S. side of the Rio Grande. In 2008, three cages were erected at Ruidosa, TX, becoming the first site with saltcedar beetles collected from Tunisia. To populate this and other sites, roughly 30 beetles were placed in a mesh cage enclosing saltcedar. Once beetle populations reached 500-1000 they were released into the open, with a few reserved to populate other sites.

The release of beetles in the spring of 2009 became the start of something unpredictable. With the help of Big Bend Ranch State Park, Big Bend National Park and private landowners, several release sites were selected along the Rio Grande River between Candaleria and Big Bend National Park. By the end of October, ARS observations concluded that the beetle populations appeared likely to establish and were predicted to defoliate five miles of river frontage within the next year (DeLoach et. al., 2009). Weather patterns of 2010, along with the all-night buffet of saltcedar, played in favor of the little warriors and their population increased exponentially. By late August, the saltcedar beetles had defoliated 20 river miles of the Rio Grande and 10 river miles of the Rio Conchos, blowing predictions out of the water.

Take a drive down the River Road (FM 170) and you'll see remnants of the saltcedar beetles' work as brown, leafless shrub -like trees that line the river's banks. While only time will tell the final story of the Rio Grande, the saltcedar beetle gives us hope - hope that in time, native cottonwoods and willows will once again flourish along the grassy banks and the river will still be enjoyed by generations to come.

REFERENCES

DeLoach, C. Jack, Allen E. Knutson, Patrick J. Moran, James H. Everitt, Gerald J. Michels, Mark A. Muegge, Charles W. Randal, Tyris G. Fain, Mark P. Donet, and Chris M. Ritzi. 2009. Progress on Biological Control of Saltcedar in the Wester U.S.: Emphasis – Texas 2004-2009. USDA/ARS-APHIS.

DeLoach, C. Jack and Allen E. Knutson. 2004. Progress in Biological Control Of Saltcedars (Tamarix Spp.) in the United States Using Control Insects from the Old World. USDA/ARS, Temple, TX.

Kristi is a Natural Resource Specialist with the Parks Division working out of Davis Mountains State Park.

21st Century Dinosaurs - Horned Lizards in West Texas

By Lee Ann Linam

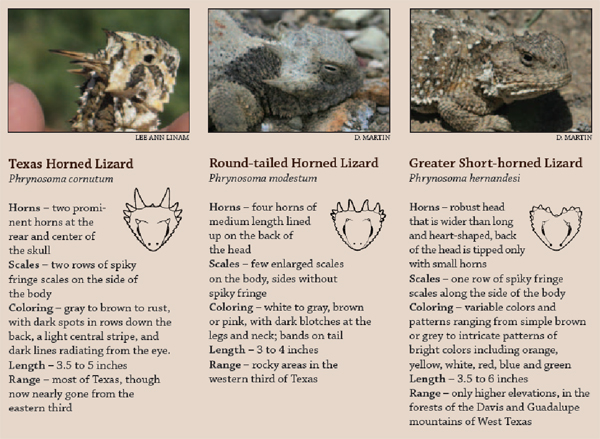

Horned lizards are named for the crown of horns found on their heads, the size and number of which vary among species. Although often called horned toads, horny toads, or even horned frogs because of their wide, flattened bodies (their scientific name Phrynosoma actually means "toad-body"), they are not amphibians like other toads, but are reptiles with scales, claws and young produced on land. More than a dozen different species of horned lizards are found only in western North America.

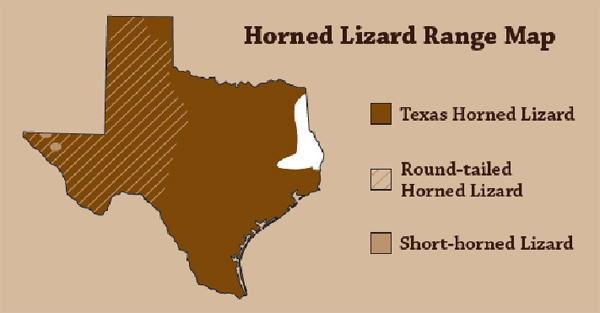

Three horned lizard species call Texas home, with the most widespread being the Texas Horned Lizard, or the familiar “horny toad.” The geographic range of these species can overlap in West Texas, but they can each be readily distinguished from each other by the type of horns on the head and the arrangement of spiny scales along the side of the body.

In addition, the three species occupy different habitats. Greater short-horned lizards, also called mountain short-horned lizards, occur only in the cooler elevations in the mountains of the Trans-Pecos, including the Davis Mountains and Guadalupe Mountains. Round-tailed horned lizards occur in open, rocky habitats in the western half of the state. Texas horned lizards, our familiar state reptile, is the most widespread—occupying a variety of open to semi-closed habitats, usually with loose soils.

Horned lizards primarily eat ants, especially harvester ants (often called big red ants), but their diet also includes termites, other insects, spiders and sowbugs. Horned lizards or their droppings can sometimes be found near the beds of harvester ants, and an individual can consume 70–100 harvester ants per day (one reason they are difficult to maintain in captivity!). Another good

As reptiles, horned lizards are ectothermic, or “cold-blooded”—depending on their surroundings to maintain their body temperature. Often burrowing overnight, they sometimes begin their day by exposing only their heads to sunlight while keeping their bodies buried. Later, they will often be seen in a flattened body posture sunning themselves in open areas. They are not usually active at night or when temperatures fall below 75° F. In general, they are seen only in late spring through early fall and tend to hibernate a few inches underground from September/October to March/April.

Mating occurs soon after emergence from hibernation. The female digs a hole 6 to 8 inches deep and lays 13 to 50 eggs (6 to 18 for round-tailed horned lizards), which are incubated by the warmth of the soil. Depending on ground temperatures, young horned lizards about 3/4-inch in length may begin to hatch 5 to 9 weeks later. The short-horned lizard, which lives in cooler, higher altitude climates, is unique among our species in giving birth to live young!

Although snakes, mammals and birds prey on them, horned lizards have developed some unique defenses. Their spiky appearance and coloration help Texas and short-horned lizards to blend into the local vegetation, while the color and shape of the round-tailed horned lizard actually help it to look like a rock! In addition to the deterrence that the horns on the head may provide to predators, horned lizards can inflate themselves to a larger apparent size or may tilt their body to appear larger. Finally, the horned lizard is renowned for its ability to shoot a stream of blood from its eye when under extreme stress (actually from ruptured blood vessels in the sinuses near the eyes). A chemical in the blood is especially distasteful to canine predators. Texas horned lizards and short-horned lizards are known to engage in blood-squirting, while the round-tailed horned lizard does not.

Whether you call it a horned frog, a horny toad, or a horned toad lizard, the horned lizard is probably Texans’ favorite reptile. Many people tell fond stories of growing up playing with horny toads. In fact, in recognition of that affection, in 1993 the Texas state legislature named the Texas horned lizard as the official state reptile.

But all is not well in this unusual love story. For many Texans, the ferocious-looking, but docile, lizard is now only a childhood memory.

Once scattered across most of Texas (and into Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and northern Mexico), Texas horned lizards have disappeared from much of the state. According to anecdotal accounts, declines began in the 1950s, and accelerated during the 1970s. At the same time, human populations were increasing, road-building and urbanization was rapid, persistent pesticides were still common in the environment, and red imported fire ants were spreading across the state. Probably as a result of the interaction of many of these factors, horned lizards are now primarily restricted to West and South Texas and to some of the state’s barrier islands. Because of these declines and concerns about overcollection for the pet trade, in 1977 Texas Parks and Wildlife Department listed the Texas horned lizard and short-horned lizard as threatened species.

Knowing that many Texans are concerned about horned lizards, in 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife Department initiated a volunteer program called Texas Horned Lizard Watch. The goal of the program is to get Texans involved in gathering data about where horned lizards still do or do not exist and the habitat that supports them and then to have those “citizen scientists” monitor changes taking place over time. More information about the monitoring program, including a downloadable monitoring packet and a summary report from the first 10 years of the program, can be found at www.tpwd.state.tx.us/hornedlizards/. Casual reports of horned lizard sightings are also welcome at hornedlizards@tpwd.state.tx.us.

Leeann coordinates the Texas Horned Lizard Watch for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department out of Wimberley.

Vegetation Changes

By Calvin Richardson

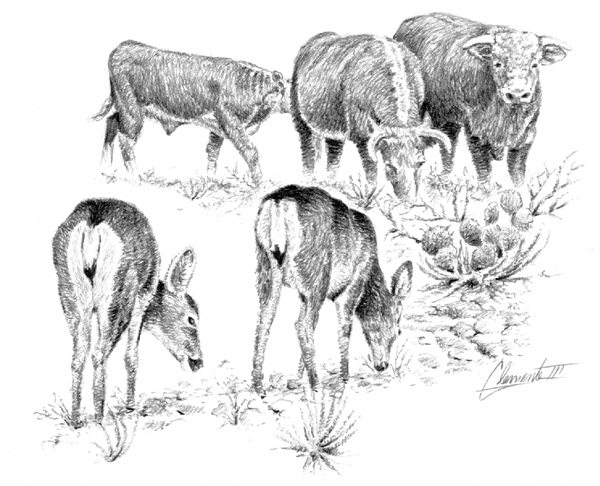

All early accounts provide evidence that the Trans-Pecos grasslands were quite expansive and that grasslands were lightly interspersed with shrubs and desert succulents (Bartlett 1854, Parry 1857, Echols 1860, Bray 1901, Cottle 1931, Humphrey 1958, Wondzell 1984, Hall 1990). Waste-high grass was reported along Terlingua Creek and in Tornillo Flats (Echols 1860), where eroded desert exists today. Extensive grass cover was described in the Big Bend area about 1900 when high numbers of livestock were being grazed in the region (Langford and Gipson 1952). In 1885 Terlingua Creek was described as a running creek full of beaver and lined with cottonwood trees (Wauer 1973, Wuerthner 1989). Evidently, mesquite was not nearly as abundant or widespread as today, existing only as scattered shrubs among the grasslands and occurring in small isolated stands (Humphrey 1958, Johnston 1963). There is no mention of the dense stands of whitethorn acacia or catclaw mimosa that dominate some areas of the Trans Pecos today. One account in the early 1850's from the Pecos River near Horsehead Crossing noted that there were no trees or shrubs along the banks of the river (Humphrey 1958). Today, the Pecos River at Horsehead Crossing is choked with saltcedar, mesquite, and other woody plants.

By all accounts, it is evident that desert grasslands throughout the southwestern United States, including the Trans-Pecos Region, have changed since Anglo settlement. Furthermore, it is well documented that grasslands have decreased and given way to increases in woody plant abundance and bare ground in some areas (Cottle 1931, Parker and Martin 1952, Buffington and Herbel 1965, Grover and Musick 1990). Prominent woody invaders and increasers of the low elevation desert grasslands include creosotebush, tarbush, mariola, whitethorn acacia, honey mesquite, and cacti. Prominent woody invaders and increasers of the higher elevation plains grasslands include juniper, catclaw mimosa, sacahuiste, cane cholla, adolpia, and prickly pear species. Numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate the causes responsible for the rapid changes in the vegetative communities. Most investigators attribute the increase in shrubs to overgrazing of grasslands by livestock, and considerable evidence has been cited in support of this concept (Humphrey 1958, York and Dick-Peddie 1969, Grover and Musick 1990, Gillis 1991). Several additional factors have been hypothesized as contributing significantly to vegetation changes in semi-desert grasslands. The factors most often considered, in addition to heavy grazing, are changes in climate, suppression of grassland fires, short and long drought periods, plant competition, and erosion of topsoil in areas where vegetation has been removed. All of these factors probably have been and are contributing to a reduction in desert grasslands and an increase in shrubs.

Healthy grassland savannas exist today on sites where wildfires have occurred or where prescribed burning is practiced, as well as on ranches that have been conservatively grazed and properly managed for decades. Most of these healthy grassland savannas occur at moderate to high elevations (cooler temperatures and greater average rainfall) in Hudspeth, Jeff Davis, Presidio, and Brewster counties.

Early Ranching Activity

Livestock grazing in the southwestern United States dates back to the 1500’s (Humphrey 1958, Bahre 1991). In the mid-1500’s cows, sheep, and horses were brought into the southwest from Mexico. Some of the animals were lost or strayed and gave rise to feral herds that grazed the region. The number of cattle, sheep, and horses increased steadily after 1598, although for many years Indian hostility forced the herders to concentrate their grazing activity near the towns of El Paso, Santa Fe, Taos, and Tucson (Humphrey 1958). Spanish missionaries and farmers gradually increased the number of sheep and goats along the Rio Grande between El Paso and present day Presidio, herding sheep into the Trans-Pecos high country during the summer (Carlson 1982). The number of sheep and goats gradually declined after 1767, when the Spanish decided to retreat from most of Texas and New Mexico. In the Big Bend region, Milton Faver was reportedly the first Anglo rancher, who moved into southern Presidio County in 1857. He subsequently built a sizeable cattle herd (10,000-20,000 head), along with 5,000 sheep and 2,000 goats.

Extensive ranching in the Trans-Pecos began in the early 1880’s when the first Anglo Americans settled in the Big Bend region. Livestock numbers peaked in the late 1880’s soon after completion of the Texas and Pacific Railroad (in 1883) through the region. By 1885 relatively large herds of livestock were being raised in the Trans-Pecos. But it was not long before drought and severe winters (1885-1895) drastically reduced the herds. Many of the cattle companies that began their operations in the 1880’s were out of business by 1905. Range conservation and management was born subsequent to the "apalling" losses of cattle from drought and starvation, the lowered rangeland productivity, and "the associated evils of soil erosion, water loss, and encroachment by noxious weeds" (Gould 1951).

Given the descriptions of the vegetation by early explorers, it is not difficult to understand what attracted these early ranchers to the Trans-Pecos region. For example, Juan Mendoza in 1864 (in present day Presidio County) describes "a beautiful plain, with plentiful pasturage of couch grass." Captain John Pope in 1854 described the Trans-Pecos area as " . . .destitute of wood and water, except at particular points, but covered with a luxuriant growth of the richest and most nutritious grasses known to this continent. . . The gramma-grass, which exists in the most profuse abundance over the entire surface of these table-lands is nutritious during the whole year, and . . . seem intended by nature for the maintenance of countless herds of cattle" (Weniger 1984). What the early ranchers could not have understood is the complexity of interacting factors that allowed this sensitive ecosystem to support the vast expanses of grasslands and grassland-savannas. The first settlers were probably unaware of the brutal droughts that frequently occur in this region. They probably did not comprehend the critical role of periodic natural fires in maintaining the health and integrity of the grassland systems. Finally, a concept they could not have understood is that an ecosystem maintained by frequent drought, periodic fire, and very low numbers of grazing animals is not capable of supporting high numbers of grazing animals on a continuous or long-term basis without rangeland degradation.

To provide some idea of the livestock densities that were grazed in the region, some specific examples are described below (present day stocking recommendations normally range from 75 to 200+ acres/animal unit[1]):

- In 1881 the Iron Mountain Ranch near Marathon was stocked with 27,000 head of sheep on 45,000 acres, a stocking rate of 8.3 acres/animal unit (Clayton 1993).

- In the mid-1880’s, Lawrence Haley was running 15,000 sheep on 37,000 acres south of Alpine, a stocking rate of 12.3 acres/animal unit (Carlson 1982).

- In the mid-1890’s, the Downie Ranch in Pecos County was stocked with 20,000 head of cattle, 80,000 sheep, 2,000 goats, 500 horses on 234 sections, a stocking rate of 4.1 acres/animal unit (Downie 1978).

- In the mid-1890’s, the Western Union Beef Company stocked 400 sections near Fort Stockton with 30,000 head of cattle (8.5 acres/animal unit), but only 22,000 head (11.6 acres/animal unit) could be found in 1897 after the Indians, rustlers, and predators had their share (Downie 1978).

[1] 5 sheep = 1 animal unit, 6 goats = 1 animal unit, 1 cow = 1 animal unit, 1 horse = 1.5 animal units

The high stock densities during the 1880's and 1890's certainly had an impact on vegetation and on rangeland productivity, including soil erosion - as was indicated by descriptions of drought and starving animals. However, high stocking rates in many areas of the Trans Pecos during the next 4 or 5 decades continued to deteriorate rangelands and permanently reduce rangeland productivity. Sheep and goat numbers in the Trans Pecos gradually increased during the early 20th century and peaked in the 1940's. The sheep and goat industries in West Texas remained strong through the 1950's and 1960's and then steadily declined.

Suppression of Grassland Fires

Historically, fire played a major role in shaping and maintaining the Trans-Pecos grasslands (Wright and Bailey 1982, McPherson 1995, Frost 1998, Van Auken 2000), just as fire has influenced and maintained other grasslands of North America. Although periodic fire is an integral component of healthy rangelands, it is not the only process that has shaped the grasslands and savannas of the desert Southwest. Frequent drought, insects, disease, rodents, rabbits, and other browsers/grazers serve a role in maintaining grassland integrity by interacting with fire to control woody plants. In the absence of fire, grasslands gradually revert to dominance by woody plants. In arid environments, grass plants can often survive during drought and they thrive during periods of good rainfall with 2 very important provisos: 1) the density of shrubs and succulents (cholla, yucca, cacti, etc.) does not become excessive and 2) top-removal of grass plants does not occur too frequently.

Fire is a natural mechanism for controlling encroachment by woody plants and succulents, involving only periodic top-removal of herbaceous vegetation (7-12 year frequency in the higher elevations; 10-20 year frequency in the desert grasslands). If woody plants are allowed to increase, their deep, spreading root systems eventually out-compete grasses with the interacting effect of repeated droughts. If grass plants are continually defoliated (e.g., continuous heavy grazing), the photosynthetic structures (green leaves) are not allowed to replenish root with starches and carbohydrates. The result is declining root health, weakened plants, and eventual mortality, especially during drought. In addition, excessive grazing pressure prevents reproduction of herbaceous plants, especially problematic in areas of frequent and persistent drought.

The greatest impact of reduced herbaceous cover, whether through overgrazing, woody plant competition, or their combined effect, is exposure of bare soil. When the soil surface is not covered by grasses/forbs and exposed to the elements (wind and rainfall), erosion is inevitable. The immediate effect of increasing bare ground is substantial loss of water that otherwise would be conserved through soil infiltration, deep percolation, and absorption by grass roots. The loss of grass cover and increasing loss of water through runoff (reduced percolation into water table) is the primary reason that Trans-Pecos springs and creeks described in historical documents have dried up (the increasing number of water wells developed for irrigation, livestock, and human use also contributed to the problem). Another “immediate” effect is that exposed soil quickly becomes encrusted or "capped," which hinders water infiltration, moisture retention, and seed germination. The long-term effect of increasing bare ground is soil loss through erosion, which reduces the capability of the land to support vegetation and permanently decreases the carrying capacity of the land for livestock and wildlife.

A less apparent effect of fire suppression and heavy grazing pressure in West Texas is a gradual shift in species composition of herbaceous plants. Deep-rooted perennial bunchgrasses (blue grama, sideoats grama, bluestems, Arizona cottontop, tanglehead, green sprangletop, tobosagrass) gradually give way to less desirable, shallow-rooted species (threeawn, burrograss, fluffgrass, red grama, slim tridens). Not only do the leafy bunchgrasses receive more pressure through repeated selection by grazers, but perennial bunchgrasses are fire tolerant (fire dependent, to some extent). The growing points of most bunchgrasses are protected beneath the soil, and periodic fire tends to stimulate seed germination of perennial, warm-season bunchgrasses. Timely grazing deferment and periodic fire can reverse this trend in the species composition of herbaceous plants. Although shallow-rooted species are better than bare soil, the value of maintaining deep-rooted bunchgrasses is 2-fold: 1) bunchgrasses support greater livestock numbers and greater wildlife numbers and diversity, and 2) bunchgrasses are superior in maintaining the soil hydrology (better water infiltration, retention, and deep percolation)

Today, the most common barrier to wildfire in desert grasslands is inadequate quantity and continuity of fine fuels. Livestock grazing over the past 120 years has reduced the herbaceous biomass enough to prevent the spread of fire in most years. Other constraints on the use of fire as a management tool include lack of knowledge about fire benefits, lack of experienced assistance, liability concerns, potential threat to ranch facilities and structures, and short-term financial considerations associated with grazing deferment before and after the fire. Opportunities currently exist for use of prescribed fire in desert grasslands to prevent further shrub invasion and, to some degree, reverse the trend. In many areas of the Trans-Pecos, however, a major reclamation program involving brush control and grazing deferment would be required to partially restore desert grasslands before fire could be implemented in a management program.

Current Habitat Management Practices

For long-term benefits to wildlife in West Texas, no habitat management practices are more important than those that restore and/or maintain healthy, native, herbaceous vegetation. Every wildlife species in the Trans-Pecos, whether a game or nongame species, depends upon grasses and forbs to satisfy at least one essential requirement — whether it’s nesting cover, fawning cover, nutritious "greens," seeds, insects, or a source of water. Just as important, grasses and forbs stabilize the soil and conserve precious moisture that comes infrequently. And certainly not least, herbaceous plants provide fuel for prescribed fire, the only "natural" tool and the lowest cost practice for long-term prevention of shrub encroachment.

The emphasis on the restoration and maintenance of herbaceous cover (grasses and forbs) does not diminish the importance of trees, shrubs, and desert succulents. Prior to settlement in the late 1800’s, woody plants and succulents were sparsely scattered across the desert grasslands, with increased abundance along wet draws, rocky outcroppings and steep slopes. Their extensive root systems serve the important function of stabilizing soil on these potentially erosive sites (these areas seldom burn and are unable to support protective stands of grass). Woody plants also provide valuable food and cover for many wildlife species and livestock. Woody plants shift from a valuable habitat component to an ecosystem threat only when one or more of the "balancing" processes are removed (e.g., fire or herbaceous vegetation via overgrazing).

Maintenance of healthy grasslands and savannas in West Texas is best accomplished through periodic fire and timely light to moderate grazing, limited to years during and after favorable rainfall. Prescribed fires promote perennial forbs and perennial, warm-season bunchgrasses and prevent detrimental increases in woody shrubs. Repeated prescribed fires during the proper season (late spring or early summer) can inflict mortality on woody species that have already encroached in desert grasslands (restoration will initially require greater fire frequency than that occurring historically for grassland maintenance). Light to moderate grazing during favorable years, using no more than 1/3 of grass production (Holechek et al. 1994), will allow use of excess forage production without weakening root systems and causing plant mortality during drought years. Flexibility with livestock numbers and grazing deferment are critical tools in managing vegetation in the Trans Pecos where weather fluctuations are more dramatic than in any other region of Texas.

Degraded rangelands where soils and water (precipitation) are being lost annually can often be improved through a number of soil and water conservation techniques. Erosion control techniques such as water diversions and sediment traps should be implemented. Header dams, rangeland ripping (Ueckert and Petersen 2002), and berms are water conservation techniques that can partially restore the hydrology on specific sites and initiate seed germination. Other habitat improvement practices that may apply to specific situations in the Trans Pecos include the following:

- Mechanical brush management

- Chemical brush management

- Riparian habitat management (fencing to control time/intensity of grazing; native shrub and tree planting; control invading shrub species)

- Grazing management (light to moderate grazing in favorable years; pasture deferment)

- Water distribution

- Improved water access for birds and small mammals

- Windmill/trough overflows to create oases of green forbs/grasses, seeds and insect production

- Irrigated food plots

- Fence modification to allow unimpeded movement of pronghorn antelope and bighorn sheep

- Reduction of deer in certain areas where numbers are high

- Reduction of exotic or feral animals that are impacting and/or competing with native species

Acknowledgements: The following individuals provided helpful comments and suggestions on this management leaflet in draft: Ruben Cantu (TPW), Philip Dickerson (TPW), Scott Lerich (TPW), Steve Nelle (NRCS), Mike Sullins (TPW), Misty Sumner (TPW), and Jason Wrinkle (TNC).

Literature Cited

Bahre, C. J. 1991. A legacy of change. Univ. of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Bartlett, J. R. 1854. Personal narrative of explorations and incidents in Texas, New Mexico, California, Sonora, and Chihuahua.

Bray, W. L. 1901. The ecological relations of the vegetation of western Texas. Bot. Gaz. 32:99-123.

Buffington, L. C., and C. H. Herbel. 1965. Vegetation changes on a semidesert grassland range from 1858 to 1963. Ecological Monographs 35: 139-164.

Carlson, P. H. 1982. Texas Woollybacks: The Range Sheep and Goat Industry. Texas A&M Univ. Press, College Station.

Clayton, L. 1993. Historic Ranches of Texas. Univ. of Texas, Austin.

Cottle, H. J. 1931. Studies in the vegetation of southwestern Texas. Ecology 12: 105-155.

Downie, A. E. 1978. Terrell County, Texas, its past- its people. Rangel Printing, San Angelo, Tex.

Echols, W. H. 1860. Camel expedition through the Big Bend country. U.S. 36th Congress, 2nd Session, Senate Ex. Doc., doc. 1, pt. 2, U.S. Serial Set No. 1079, pp. 36-50.

Frost, C. C. 1998. Presettlement fire frequency regimes of the United States: a first approximation. Pages 70-81 in T. L. Pruden and L. A. Brennan, eds. Fire in ecosystem management: shifting the paradigm from suppression to prescription. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, No. 20. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL.

Gillis, A. M. 1991. Should cows chew cheatgrass on commonlands? Bioscience 41:668-675.

Gould, F. W. 1951. Grasses of the Southwestern United States. Univ. of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Grover, H. D., and H. B. Musick. 1990. Shrubland encroachment in southern New Mexico, U.S.A.: An

analysis of desertification processes in the American Southwest. Climatic Change 17: 305-330.

Hall, S. A. 1990. Pollen evidence for historical vegetational change, Hueco Bolson, Texas. Tex. J. Sci. 43: 399-403.

Holechek, J. L., A. Tembo, A. Daniel, M. J. Fusco, and M. Cardenas. 1994. Long-term grazing influences on Chihuahuan Desert rangeland. The Southwestern Naturalist 39: 342-349.

Humphrey, R. R. 1958. The desert grassland: A history of vegetational change and an analysis of causes. Bot. Review 24: 193-252.

Johnston, M. C. 1981. Past and present grassland of southern Texas and northeastern Mexico. Ecology 44:456-466.

Langford, J. O., and F. Gipson. 1952. Big Bend, a homesteader’s story. Univ. of Texas Press, Austin.

McPherson, G. R. 1995. The role of fire in desert grasslands. Pages 130-151 in M. P. McClaran and T. R. Van Devender, eds. The Desert Grassland. The Univ. of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Parker, K. W., and S. C. Martin. 1952. The mesquite problem on southern Arizona ranges. Circular No. 908. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

Parry, C. C. 1857. In Emory, W. H. 1985. United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. U.S. 34th Congress, 1st and 2nd Session, Senate Ex. Doc., doc. 108, vol. 2, pt. 1, U.S. Serial Set. No. 833, pp. 9-26.

Ueckert, D. N., and J. L. Petersen. 2002. Water conservation for restoration of wildlife habitats. Pages 101-114 in L. A. Harveson, P. M. Harveson, and C. L. Richardson, eds. Proceedings of the Trans-Pecos Wildlife Conference. Sul Ross State Univ., Alpine.

Van Auken, O. W. 2000. Shrub invasions of North American semiarid grasslands. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 31: 197-215.

Van Devender, T. R. 1995. Desert grassland history. Pages 68-99 in M. P. McClaran and T. R. Van Devender, eds. The Desert Grassland. The Univ. of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Wauer, R. H. 1973. Naturalist’s Big Bend. Texas A&M Univ. Press, College Station.

Weniger, D. 1984. The Explorers’ Texas: The Lands and Waters. Vol 1. Eakin Press, Austin, Tex.

Wondzell, S. M. 1984. Recovery of desert grasslands in Big Bend National Park following 36 years of protection from grazing by domestic livestock. M. S. Thesis, New Mexico State Univ., Las Cruces.

Wright, H. A., and A. W. Bailey. 1982. Fire ecology: United States and Southern Canada. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Wuerthner, G. 1989. Texas’ Big Bend country. American Geographic Publishing, Helena, Mont.

York, J. C., and W. A. Dick-Peddie. 1969. Vegetation changes in southern New Mexico during the past 100 years. Pages 157-166 in W. G. McGinnies and B. J. Goldman, eds., Arid Lands in Perspective. Univ. of Arizona, Tucson.

Calvin is Wildlife Division District 2 Leader working out of Canyon.

Volunteering at the Big Bend Ranch State Park:

How I got here

By Gary Nored

Not. By all rights I should have nothing but unpleasant memories of that trip. I started out by getting lost. I took such a bad fall that I serious doubts for awhile that I was ever going to be able to get out from under my pack. I left without any warm gear and spent most of a day cold and wet. I ultimately ran out of water and came perilously close to dying out there. If I hadn't been good with a map and compass, and enjoyed great fortune in finding water at Rancheria Spring, I would have. But it was my second night, after the storm cleared that changed my life and brought me to where I am today.

I stopped on the upper end of the lower Guale Mesa, quite close to the rim of Tapado Canyon. I set up my camp and then walked to the edge of the canyon to watch the sunset. One would think that I’d be somewhat dispirited by now, but I wasn’t. The sunset was one of those those that you never forget. The view down the canyon of the mountains in Mexico is stunning any time, but with the storm clouds it was simply magnificent. That night, sitting on the rim of the canyon it happened. I realized that walking through this area once, or even several times would not be enough. I was going to have to come out here and spend some serious time … real time … like years.

Well, I did.

Of course, many things have to happen between deciding something like this and actually doing it. Suffice it to say that I did all that. Less than a year after I retired I was in West Texas determined to help make a many people’s lives better rather than making a few people’s more wealthy. I started by taking a little detour – to Alpine. I’d intended to stay only as long as it took for me to get on at the ranch, but when I started volunteering at the Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute I settled in Alpine.

I did many things for CDRI, but the most personally rewarding was writing Nature Notes. When the man who had been doing it before left for another job, I took over and authored the show until his replacement could be found. It was almost a full-time job for me. Not being a trained biologist I had to do a lot of research, both to find topics and to ensure the accuracy of the things I said. But I like research and soon I was meeting people who’d heard one of my programs or read something I’d done somewhere and that was very gratifying.

I was still thinking about the Big Bend Ranch. I’d written and gotten no reply and was beginning to think that maybe I didn’t have the skills they wanted. I was wondering if there was anything I might do to make myself more useful to the park when I learned about the Texas Master Naturalist program. This program trains people as “master naturalists” to help them be better volunteers. Perfect! I signed up with the Tierra Grande chapter.

The Tierra Grande Chapter of Texas Master Naturalists serves some of the largest counties in Texas – Jeff Davis, Brewster and Presidio. It partners with with the Texas Agrilife Extension Service, The Nature Conservancy, Sul Ross State University, CDRI, Big Bend National Park and Texas Parks and Wildlife. Needless to say, the opportunities for meeting natural resource people in such a group are excellent, and meet them I did. Though I hadn’t thought of it when I joined, in retrospect I’ve come to realize that the chance to meet all these people was just as valuable as the formal training I received.

In my mind, the formal training became one of those “life experiences,” a memory I will hold to my final days. The training was informative, exciting, and intense. Very intense. Our instructors were people whose books I owned or whom I had heard about as creatures of naturalist legend. The class time was wonderful, the field work amazing. My classmates were all extremely interested in the course material. They were motivated, intelligent, and wonderfully friendly.

The field work was also physically demanding. On our hike up Mt. Livermore I learned how friendly, supportive, and understanding West Texans can be. About two thirds of the way up I thought I’d gone about as far as I could. The slopes are steep, the rocks loose, and there’s no air up there! On this Texas version of the Bataan Death March I fully expected to be thrown over the side at any moment and my body left for the vultures. I ate my lunch thinking that it was pathetic for a man’s last meal to be a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. I was thus contemplating my mortality when one of my classmates, whom I knew from CDRI, came over and started giving me a pep-talk. I was having none of it. But he persisted. He reminded me that I’d never be any younger. He reminded me that I might never have another chance to see this remarkable place. He said he’d help me, and then, without so much as a by your leave, he snatched up my backpack and pulled me to my feet. I gave up – resistance was futile.

For the rest of the climb he carried my pack. He kept me from falling on rocky slopes, and physically dragged me up those I couldn’t manage. And he got me to the top – alive. I’ll never forget the view, or his wonderful kindness.

I became thoroughly settled in Alpine, but one day I realized that I hadn’t been to Big Bend in over a month, and I wasn’t doing anything for the park. The illecebrous qualities of settled living had taken advantage of my natural tendencies towards sloth and indolence and my root system was already starting to grow. That would never do!

I renewed my assault on the park. When nothing came of email and calls, I decided to be more assertive. I drove down to the park and, shortly before 5:00, planted myself at the front door of the visitors center informing the staff that nobody was leaving the building until I talked to the head ranger. It worked … after a fashion. He gave me some forms to fill out and told me that I could come back after they were processed.

They were never processed. After two or three months of waiting, I went down to the Barton Warnock center and discussed the matter with the rangers there. There I learned that the park had a new superintendent who had only arrived the day before. They suggested I talk to him. I immediately drove over and met the new superintendent, Barrett Durst, who recognized my name as one of those his foot-deep in-box. We had a nice visit, and within a week the forms had been processed and a date set for my arrival.

I don’t know if you’ve ever been through the mountains at the Big Bend Ranch State Park, but it would be no exaggeration to say that the drive is always “interesting” It took me over six hours to pull my trailer from Presidio to Sauceda headquarters, and at that, I took it way too fast. I’d overlooked the securing of one or two things, and a couple of the additions I’d made to hold things in place failed. After I’d gotten the beast parked and leveled, I opened the door to a scene straight out of Lucile Ball’s The Long, Long Trailer. The restraints for the microwave and toaster oven failed, so they were on the floor. The fastenings for the refrigerator failed, the door fell off, and broken food containers spread beans, pickles, BBQ sauce, etc., from front to back. I’d forgotten to latch the “little stuff” drawer, so pill bottles, pins, screws, tweezers, toothpicks, and all manner of other small objects had enjoyed a veritable orgy wallowing in the food on the floor. The 12 Volt power supply for the refrigerator had broken, as had the igniter for the propane, so that had to be fixed immediately. There were a bazillion other things that needed attention, and as one who is mechanically challenged, I was hard put to set everything aright.

But everything did get fixed and soon I was tending the grounds, fixing signs on the nature trail, rooting out invading species from the visitor center gardens, and generally doing everything I could to make the park a better place for my being there. And I was learning … a lot.

One of the first things I learned is that there is a world of difference between visiting a place on vacations and actually living there. The life skills needed to get along out here are totally different from those needed to get along in the city. For example, if you have a flat in the city you just pick up your cell-phone, dial Acme fix-it company, and they come out and fix it. If you get stranded somehow, you just call one of your many friends and they come get you. It’s different here …

When something breaks out here you have to deal with it. There is no Acme fix-it company. You can’t call a friend and be picked up in 30 minutes or so. It takes hours to get anywhere from here. For better or worse, out here you’re pretty much on your own. But not really. Here, if you don’t know how to do something, somebody will teach you, and help you learn. If you get stuck somewhere, nobody will pass you by. The friendly help and encouragement I’d gotten on Mt. Livermore was not the provenance of a single person – it is just the way people are out here. There’s a friendly, cooperative make-do kind of spirit out here that is life-affirming and altogether more positive than anything I ever felt in the high-tech world.

Right away I learned that the term “park host” means different things in different places. Here at the ranch it does not mean hanging out at the entrance and helping people move their “mobile homes” around in the parking lot. In the summer it means tending grounds, laying floors, repairing fences, and clearing trails. In the winter it means making beds, cleaning facilities, washing dishes, doing laundry and taking care of visitors

I also learned that old Airstream trailers are not very well insulated. With the air-conditioner running full tilt I was just able to cool mine down to around 95º. Needless to say, I didn’t spend much time there in the afternoon.

Heat is another integral part of desert life in West Texas. It’s everywhere, it’s all of the time, and there’s no getting away from it. It saps your strength, sucks every drop of moisture out of you, and if you’re working in the sun, it can even be lethal. You have to learn how to deal with it – to pace your work – to take breaks – to drink lots of water – to dress properly – to recognize the signs of heat stress and to act accordingly. None of this stuff can be learned by reading – you can only learn by experience.

Our low humidity can make you feel cooler than you are, and that can be dangerous. During my first summer I succumbed to heat exhaustion during a trail-building exercise. After a few hours of chopping brush and hauling rock I suddenly started feeling weak and very tired. Within moments I couldn’t stand up, so I found a rock and sat down. Soon, that wasn’t enough, so I rolled off the rock and spread out on the ground. I didn’t feel any better, but at least I couldn’t fall. Fortunately, the crew chief happened by, realized immediately what was going on and got me into some shade with a bottle of water. If he hadn’t come by I would have died there.

Since then I’ve had all the usual troubles – runaway horses, nasty falls, lost in the wilderness – but I’ve never stopped having a good time. I’ve learned enough about the area that I can now give tours, showing people the sights and explaining the unique environment that exists here.

When someone in Austin happened to like one of my photographs, word spread to state offices and now I take a lot of pictures for the park. My long-term project is photo-documenting every campsite in the park. We’re creating a book for the front desk so that visitors can look at pictures when they’re picking out a campsite. I’m also doing “rent-a-ranger” tours. I take people out to interesting places and talk about the park’s plant life, wildlife, geology, and history. Last year I happened to notice that there were many photographers coming to the Photo Safari who really only wanted a chance to visit areas that are difficult to reach. That gave me the idea of offering “Photo Tours” where we take photographers out to some of the most scenic areas in the park and camp overnight. The program is already a big success – the rest of the season is sold out.

Life is now settled into something of a routine, but I love every minute of it. I continue to read about and study the area. I accompany botanists and geologists on their trips greedily soaking up anything I can learn from them. I’ve learned to take pleasure from a house-cleaning job well done, and to love feeding hungry hikers and hearing of their adventures. I’ve “rescued” a few people from serious situations, carried tired children down icy slopes, led hikes, doctored injured horses, learned to change oil, fix tires, and do things with bailing wire I would formerly have thought impossible. For entertainment I chase longhorns out of the front gardens. They’re not afraid of me, but I like making all those noises one used to hear cowboys make in old westerns. I guess you might say that I’m putting down a new root system.

Best of all, over 20 years since I first saw it, I’m taking people to view Tapado Canyon from the very spot where I first fell in love with this park. The excited exclamations groups make when they first behold this sight are worth more to me than all the gold in Peru.